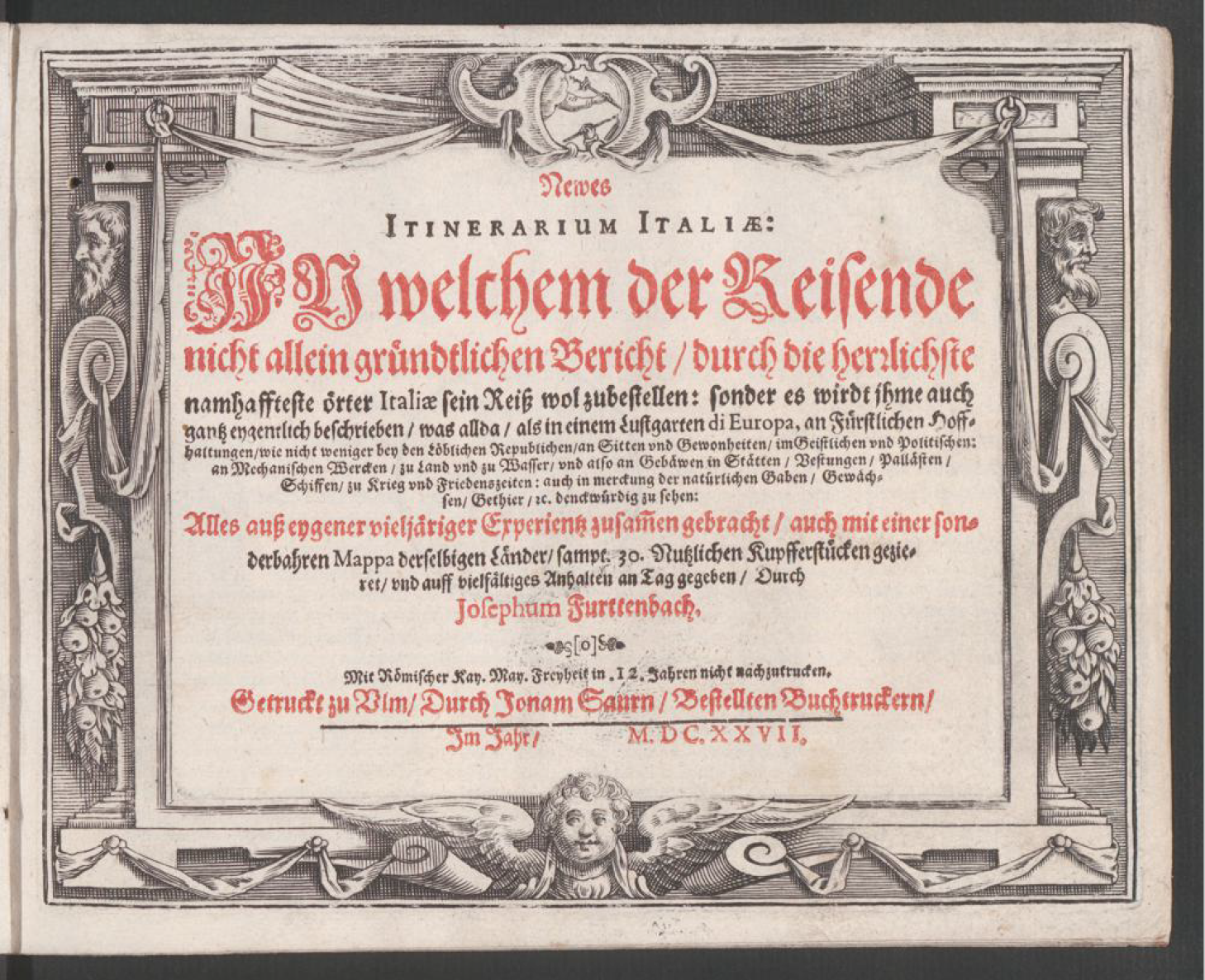

Joseph Furttenbach’s Newes Itinerarium Italiae differs from other travel guides or diaries about Italy written by his English counterparts. Whereas most English travel logs written in the seventeenth century were based on notes taken by aristocratic Englishmen or their traveling companions during their Grand Tour of continental Europe, Furttenbach migrated to Italy and stayed there for 12 years. Following in the footsteps of his relatives, he did an apprenticeship as merchant, and during his stays in Milan, Genoa and Florence, he travelled to various places.[1] He also studied engineering and architecture while abroad and later built a successful career as an architect after returning to his home country, Germany. Although his time in Italy would have been occupied with work and family business rather than leisure activities, his book is written to be read as travel literature as the title suggests. He specifically uses the word “Reiß” (which means travel in German) to describe his experiences. Historian Roberto Zaugg has pointed out that Furttenbach consciously promotes himself as a cultural mediator between Italy and Germany by filling his book with the details of the architecture of churches, palaces and theaters.[2] Engravings of the buildings and ground plans show how Furttenbach aims to instruct and inform his readers about the architecture of Italy, thereby establishing himself as an expert in the field.[3] His description of the Camposanto reflects his attention to architectural details such as sepulchres and sarcophagi occupying the gallery, and notes that the holy earth is supposedly from Jerusalem. / DJ

[1] Roberto Zaugg, “Joseph Furttenbach als kultureller Vermittler,” in Lebenslauff 1652–1664, ed. Roberto Zaugg, Kim Siebenhüner and Kaspar von Greyerz (Cologne:Böhlau Verlag, 2013), 27-28.

[2] Ibid., 32.

[3] Ibid., 34.

Source: Joseph Furttenbach, Newes Itinerarium Italiae (Ulm: Saur, 1627), 70.

Transcription

“Gleich darbey ist der Campo Santo, ein Creutzgang so gantz ubermahlet, von gar alten Historien und Grabschriften gezieret. In der mitten hats ein offnen Gottsacker und an seinen Seiten stehen viel alte steinerne sepulchri und Särch der Boden oder die Erden ist also beschaffen, dass die todne Cörper so man darein begräbt in 24. Stunden consumiren und verwesen also dass hernach allein die Gebein gefunden werden wie man mich berichtet so solle solche Erden terra santa, und von Jerusalem dahin geführt worden sein.”

Translation

Right next to it [close to the Baptistery] is the Campo Santo, a cloister completely

covered, adorned with very old histories and epitaphs. In the middle, there is an

open cemetery, and there are many old stone graves and coffins on the sides.

The ground, or the earth, consumes and decomposes the dead bodies buried in it in 24 hours, so that afterwards only the bones are found, as I have been told. Thus such earth is said to be terra santa,

and is said to have been brought there from Jerusalem.