Introduction

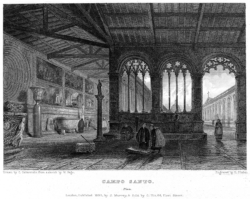

Few monuments of the European Middle Ages have been so often and so extensively described by premodern authors as the cemetery of the Piazza del Duomo in Pisa. This extraordinary richness of sources reflects the Camposanto’s unique character: erected in a time when burial places were commonly attached to church buildings, it is an imposing, independent structure, located at the very center of the city’s religious life. While it was still under construction, a legend began to circulate about how the central area of the cemetery had been filled with earth from the Holy Land. In the same period, artists began to transform the huge galleries with monumental wall paintings of unsurpassed scale and extent. Furthermore, antique sarcophagi that had been used by noble Pisan families were transferred into the building in great number. Small wonder, then, that the Camposanto soon became the pride of the Tuscan sea republic, mentioned and praised by authors of local chronicles. Even after 1406, when the city lost its autonomy and came under the dominion of Florence, the new rulers decided to appropriate this unique monument by financing the completion of the frescoes in the northern gallery. In the Renaissance, artists such as Ghiberti and Vasari held up the wall paintings as exemplary works of the rebirth of Italian art that ended the ‘dark centuries.’ Early modern pilgrims connected the Camposanto to particular sites in Jerusalem. Soon Pisa was also on the route of travelers coming from other cities and countries,and continued to be a place for tourists into the modern and contemporary period. Foreigners describing the most impressive sights of the city produced innumerous descriptions of the Camposanto.

The Building The Earth The Paintings Damage, Destruction and Restoration