The Paintings

Certainly the main reason for the Camposanto’s celebrity in modern times is the vast fresco decoration of the building. Unsurpassed in its format and extent, this ensemble of wall paintings was created over a timespan of one and a half centuries (from ca. 1336 to 1485). Perhaps the best way to look at it is to see it as a unique experiment: thanks to its monumentality, the Camposanto offered painters a framework that allowed them to think and work in spatial dimensions that existed nowhere else. And thanks to its particular function, this was also a place where the established pathways of standardized iconographic programs could be ignored.

The first fresco campaign

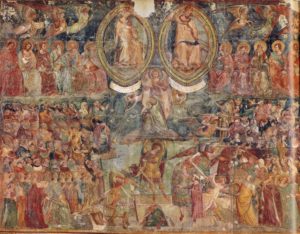

Looking at the chronology of the building process, there can be little surprise that pictorial decoration started in the southeastern section: while large parts of the building were still under construction, here the first parts of the galleries had been completed up to the roof. This was also the area that constituted the ritual and liturgical core of the cemetery – an aspect that is crucial for understanding the choice of subjects and the arrangement of the pictures: the paintings on the eastern wall show Christ’s death on the cross and his victory over death. In contrast, the frescoes on the southern wall confront the viewers with the issue of their own soul’s fate: in the center of this tripartite arrangement, the traditional subject of the Last Judgment is presented in an extremely innovative manner, with a remarkable imbalance towards the punishment of the condemned. Complementarily, the famous depiction of the Triumph of Death reminds viewers of the omnipotence and unpredictability of death, which is immediately followed by the Particular Judgment of the souls. And the Thebaid presents a large selection of scenes from the lives of the desert fathers, which viewers are meant to perceive as examples for preserving one’s own soul. Hence, there is a complementary relationship between the pictures on the east wall and those on the south wall that is also manifest on the level of the pictorial space: the Crucifixion and the Ascension contain explicit references to the individual topography of holy sites in and around Jerusalem: the rocky landscape around Mount Golgotha and the treed summit of Mount Zion clearly allude to the legend of the holy earth. In contrast, the pictures on the south wall put the mountain of Hell in the foreground that occupies one half of the Last Judgment.

As for the artists and the commissioners involved in this important part of the fresco decoration, no archival documents have survived. And in the early literature on artists (such as Lorenzo Ghiberti’s Commentaries or the Anonimo Magliabechiano) and the laudatory poem composed by Michelagnolo di Cristofano da Volterra at the end of the fifteenth century, indications of their authorship is extremely fragmentary and vague: the most frequently cited name is Buonamico Buffalmacco, but without any further specification. Against this general lack of precise information, Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574) tried to establish a more detailed picture in the second edition of the Vite (1568), where he specified the authorship of every single part of the Camposanto decoration: according to this account, the Passion cycle on the east wall had been executed by Buonamico Buffalmacco, the Triumph of Death and the Last Judgment by Andrea di Cione (Andrea Orcagna), the Hell by his brother Nardo di Cione, and the Thebaid by Pietro Lorenzetti. Due to Vasari’s long-lasting reputation and the easy accessibility of the 1568 edition, these attributions were repeated by most of the later literature that we have gathered in this blog. Only in the nineteenth century did authors such as Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle and Joseph A. Crowe (History of Painting in Italy, 1864-1866), and Igino Supino (Il Camposanto di Pisa, 1896) reject the idea of Orcagna’s and Lorenzetti’s authorship of the frescoes on the south wall. Supino’s tentative attribution to the Pisan painter Francesco Traini was later corroborated by Millard Meiss (1933) and widely endorsed by subsequent literature. Yet in 1974 Luciano Bellosi proposed an entirely different view: according to him, it was not by chance that the name of Buonamico Buffalmacco was so frequently cited by the early sources. On the basis of stylistic comparisons, he demonstrated that Buffalmacco was likely the author of the entire first fresco campaign, with the exception of the Crucifixion that is now attributed to Traini.

The western part of the southern gallery

At least initially, the Opera must have planned to have the murals of the southern gallery finished in a relatively short time: in ca. 1341/43, the first section beyond the main entrance was assigned to Giotto’s disciple Taddeo Gaddi (1290-1366). As the subject for these frescoes, a classical example of penance was chosen: the story of Job’s suffering and his final reward. Thematically, this program was perfectly in line with the earlier program of the Buffalmacco frescoes. But the layout of the Gaddi cycle marks a clear rupture with the monumental format of the first campaign: Gaddi divided the painting surface into two horizontal registers with three pictures each. This format was retained in all subsequent phases of the Camposanto frescoes.

In contrast to the swift progress of the decoration until this point, the remaining part of the southern corridor was completed only after several interruptions. In fact, it took more than three decades until frescoing resumed: only in 1376 did Pietro Gambacorta, Pisa’s powerful signore since 1370, decide to commission a cycle dedicated to the life of San Ranieri. Clearly the choice of this subject aimed at a connection between the venerated sites of the Holy Land and the civic identity of Pisa: Ranieri had been a son of a wealthy family of Pisan merchants, who after his conversion spent several years in Palestine as a pilgrim. After his return to Pisa, he continued his religious activity at the monastery of San Vito. When Ranieri died, his remains were buried in the cathedral. Hence, this cycle put the topography of Jerusalem and the Holy Land in direct correlation to the urban landscape of Pisa. Left unfinished at the death of Andrea da Firenze, the painter chosen by Gambacorta, its second part was executed by Antonio Veneziano in 1384-86.

Again, a strong local accent is present in the last section of the south wall, which is dedicated to the Sardinian martyrs Ephesus and Potitus, whose relics were said to have been transferred to Pisa in the late eleventh century, and who therefore recalled the period of Pisa’s dominion over the Mediterranean island – a chapter that had belonged to the past since 1326, when Pisa had lost its control over Sardinia. This cycle with its dramatic battle scenes was painted by Spinello Aretino in 1391/92.

The northern corridor

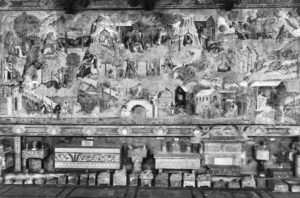

In the meantime, the construction of the northern gallery had been completed, and the Opera obviously tried to accelerate the pace of the pictorial campaign. As early as 1389, the Opera commissioned the first frescoes in the northern gallery from Pietro di Puccio from Orvieto (active between 1360 and 1402). Pietro started his work with a depiction of the Christian macrocosm. This mural translated a typical subject of diagrammatic manuscript culture to a monumental scale, a shift in format that assured this painting continuing admiration. Since most of the spherical picture was reserved for the nine choirs of angels, it could be read as a visualization of the celestial realm to which the souls of the elect would rise after death. At the same time, the painting acted as a starting point for the series of Old Testament scenes that cover the remainder of the northern gallery, the Camposanto’s most extensive narrative cycle, whose first three pictures had been painted by the same Piero di Puccio, while its continuation would only be realized about eight decades later, under Archbishop Filippo de’ Medici, who engaged one of the preferred artists of his family, Benozzo Gozzoli (ca. 1420-1497). After a long period of neglect that followed the seizure of Pisa by Florence in 1406, the Gozzoli campaign was the expression of a new interest in the Camposanto’s unique role as a monument of Tuscany’s cultural identity. In fact, the narration, with its focus on the Israelites’ role as chosen people and Palestine’s role as promised land, blends the history of salvation, the holy earth in the cemetery, and the contemporary situation of fifteenth-century Tuscany.

Bibliography

Iginio Benvenuto Supino, Il Camposanto di Pisa (Firenze: Alinari, 1896).

Millard Meiss, The Problem of Francesco Traini, «Art Bulletin» 15/2 (1933), pp. 97-173.

Luciano Bellosi, Buffalmacco e il Trionfo della Morte (Torino: Einaudi, 1974).

Caleca, Il Camposanto Monumentale. Affreschi e sinopie, in Antonino Caleca, Gaetano Nencini, Giovanna Piancastelli, Pisa. Museo delle sinopie del Camposanto Monumentale (Pisa 1979), pp. 38-115.

Antonino Caleca, Costruzione e decorazione dalle origini al secolo XV, in Clara Baracchini, Enrico Castelnuovo (eds.), Il Camposanto di Pisa (Torino: Einaudi, 1996), pp. 13-48.

Diane Cole Ahl, Camposanto, Terra santa. Picturing the Holy Land in Pisa, «Artibus et Historiae», 24/8 (2003), pp. 95-122.

David Ganz, Campo santo, campi dipinti. The Legend of the Earth and the Spaces of the Camposanto’s Early Fresco Decoration, in Michele Bacci, David Ganz, Rahel Meier (eds.), Journeys of the Soul. Multiple Topographies in the Camposanto of Pisa (Pisa: Edizioni della Scuola Normale, 2021), pp. 65-110.

Introduction The Building The Earth Damage, Destruction and Restoration