When Giorgio Vasari undertook the revision of his Vite, his aim was not simply to update and augment the first version with new and additional material – information that was provided and processed by a network of numerous correspondents and collaborators. He also reconceptualized his master narrative and reassessed the role played therein by certain monuments. The extensive account of the Camposanto’s architecture and artworks is certainly one of the most striking examples of the radical consequences of this process: whereas in 1550, the Pisan cemetery did not figure prominently, the 1568 edition declared it one of the central monuments of the Tuscan Trecento. Despite being distributed among the lives of their authors, the single passages dedicated to the Camposanto merge into one coherent account whose chronological order has been composed very carefully: while the construction of the building is still linked to Giovanni Pisano, it is now given a much earlier date, between 1278 (the year mentioned in the inscription at the entrance) and 1283. This remarkable shift in time allowed for the inclusion of the most prominent artist in part one of the Vite: none of the older sources had mentioned the name of Giotto in the context of the Camposanto fresco campaigns. By attributing the Job cycle to the Florentine artist – a work that Vasari himself had previously listed among the paintings of Taddeo Gaddi – the second edition of the Vite declared the Camposanto one of the focal points of his entire narrative: the Pisan cemetery became the place where the development of the Tuscan school of painting during the fourteenth century could be studied in every single phase; this was a process of gradual improvement, defined by the measure of Giotto’s art. Vasari’s description of the Job cycle makes it very clear that he looked at this process both in terms of artists’ capacity for imitation and their technical mastery. Due to its damp and salty air, the Camposanto was one of the places where painters were forced to apply new and better techniques of fresco painting that afforded their works a longer durability. Thus, when Vasari declares that Antonio Veneziano’s continuation of the Ranieri cycle surpasses all the other Trecento murals in the cemetery, he justifies this judgement with the painter’s superior fresco technique.

Starting with Giotto and ending with Spinello Aretino, the frescoes in the East, South and North galleries of the Camposanto offer an almost complete panorama of Tuscan Trecento painting. In Vasari’s account, three differing tendencies come to the fore: the first is the classical tradition of narrative painting in the guise of Giotto which is represented by Antonio Veneziano and Spinello Aretino; the second is a more spectacular approach linked to innovative subjects such as God Creator of the cosmos and the Triumph of Death – works which Vasari attributes to the Florentine artists Buonamico Buffalmacco and Andrea Orcagna; and the third, the differing tendencies in landscape and narrative painting developed by Sienese painters such as Pietro Lorenzetti and Simone Martini. Regarding this third tendency, one must note that Vasari’s reattribution of the wall paintings led to the creation of a “Sienese area” around the main entrance: the Thebaid was presented as a work by Pietro Lorenzetti – probably because of a certain afffinity with the wide landscapes that can be found in contemporaneous Sienese murals – while the Assumption of the Virgin and the upper part of the Ranieri cycle are now assigned to Simone Martini (perhaps due to the ambiguous title of the fresco, Vasari forgot to remove the Assumption from the list of works attributed to Stefano Fiorentino, an error which highlights the risks of the entire revision process). Here, Vasari implicitly acknowledges that the contribution to Trecento wallpainting by Sienese painters was too important to be exluded from the overall scheme.

Due to its widespread diffusion, the 1568 edition of the Vite was certainly the most influential text for the reception of the murals in the Camposanto. Not only did other artists’ biographers and historiographers describe the frescoes through the lense of this text, travellers also saw them through this lense as well. As a consequence, the almost arbitrary attributions proposed by Vasari where accepted and repeated for centuries. Yet there are also more productive aspects of this influence: the fact that Vasari gave an extremely comprehensive account of the Triumph of Death sparked the interest of visitors in this particular picture. Interestingly, what motivated the Triumph’s detailed description was not only the genre-like realism of the lovers’ garden and the hunters’ company. In fact, we know from a letter (dated 17 April 1561) written by Cosimo Bartoli (1503-1572), a philologist and translator in the service of Cardinal Giovanni de’ Medici, that Vasari had explicitly asked his friend for detailed transcriptions of the texts inserted into this and other frescoes of the Camposanto. At least at this point in the revision process, Vasari seemed to be interested in the texts as key to the conception of this work and in different possibilities of image-text interplay. Yet in the end he decided to remove most of the citations provided by Bartoli and to ridicule the visualization of spoken dialogues through written texts – a device that he traces back to the artist who is nowadays considered the painter of the Triumph, Buonamico Buffalmacco. /DG

Vasari, Le vite_1568 (Nicola-Gozzoli)

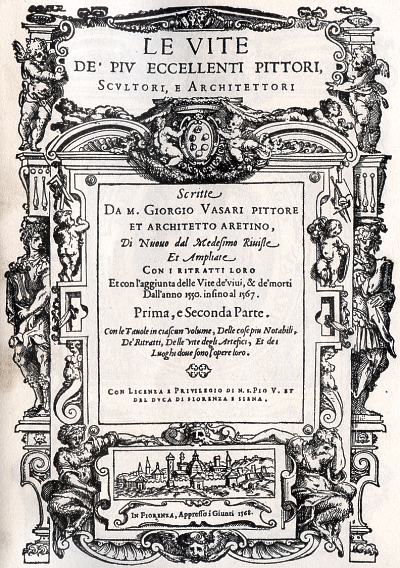

Source: Giorgio Vasari, Le vite de’più eccellenti pittori, scultori, e architettori, 2 vols. (Florence: Giunti, 1568).

Edition: Giorgio Vasari, Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori e architettori nelle redazioni del 1550 e 1568, ed. by Rosanna Bettarini, commentary by Paola Barocchi, 6 vols. (Firenze: Sansoni 1966-1987).

Translation: Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, transl. by Gaston Du C. De Vere, 10 vols. (London: Warner, 1912-14).

1.Vita di Nicola, et Giovanni Pisani, Scultori, et Architetti

Transcription

“Veduto ciò [Giovanni’s works for the church S. Maria della Spina in Pisa] i pisani, i quali molto inanzi havevano havuto ragionamento, e voglia di fare un luogo per le sepolture di tutti gli habitatori della città, cosi nobili, come plebei, ò per non empiere il Duomo di sepolture, ò per altra cagione; diedero cura a Giovanni di fare l’edifizio di campo santo, che è in sulla piazza del Duomo verso le mura, onde egli con buon disegno e con molto giudizio lo fece in quella maniera e con quelli ornamenti di marmo, e di quella grandezza, che si vede, e per che non si guardò a spesa nessuna, fu fatta la coperta di piombo; e fuori della porta principale si veggiono nel marmo intagliate queste parole: A.D. MCCLXXVIII. tempore Domini Federigi Archiepiscopi pisani et Domini Sirlatti potestatis, operario Orlando Sardella, Ioanne magistro edificante. Finita quest’opera, l’anno medesimo 1283 andò Giovanni a Napoli, dove per lo re Carlo fece il Castel Nuovo di Napoli.” (1: 102)

Translation

“Seeing this [Giovanni’s works for the church S. Maria della Spina in Pisa], the Pisans, who long before had had the idea and the wish to make a place of burial for all the inhabitants of the city, both noble and plebeian, either in order not to fill the Duomo with graves or for some other reasons, caused Giovanni to make the edifice of the Camposanto, which is on the Piazza del Duomo, towards the walls; wherefore he, with good design and with much judgment, made it in that manner and with those ornaments of marble and of that size which are to be seen; and because there was no consideration of expense, the roof was made of lead. And outside the principal door there are seen these words carved in marble: In the year 1278, at the time of Federico Visconti, the archbishop of Pisa, and Tarlato, the podestà, under the operaio Orlando Sardella and master Giovanni who built this. This work finished, in the same year, 1283, Giovanni went to Naples, where, for King Charles, he made the Castel Nuovo of Naples.” (vol. 1, p. 37)

2. Vita di Giotto Pittore, Scultore et Architetto Fiorentino

Transcription

“Questa tavola [= the Louvre Pala, showing the stigmatization of St Francis], la quale oggi si vede in S. Francesco di Pisa in un pilastro accanto all’altar maggiore, tenuta in molta venerazione per memoria di tanto uomo, fu cagione che i Pisani, essendosi finita appunto la fabbrica di Campo Santo, secondo il disegno di Giovanni di Nicola Pisano, come si disse di sopra, diedero a dipignere a Giotto parte delle facciate di dentro. Acciò che, come tanta fabrica era tutta di fuori incrostata di marmi e d’intagli fatti con grandissima spesa, coperto di piombo il tetto, e dentro piena di pile e sepolture antiche state de’ gentili e recate in quella città di varie parti del mondo, così fusse ornata dentro nelle facciate di nobilissime pitture. Perciò, dunque, andato Giotto a Pisa, fece nel principio d’una facciata di quel Campo Santo, sei storie grandi in fresco del pazientissimo Iobbe; e perché giudiziosamente considerò che i marmi da quella parte della fabrica dove aveva a lavorare erano volti verso la Marina, e che tutti essendo saligni, per gli scilocchi, sempre sono umidi, e gettano una certa salsedine, sì come i mattoni di Pisa fanno per lo più, e che perciò acciecano e si mangiano i colori e le pitture: Fece fare perché si conservasse quanto potesse il più l’opera sua, per tutto dove voleva lavorare in fresco, un arricciato, o vero intonaco, o incrostatura che vogliam dire, con calcina, gesso, e matton pesto mescolati, cosi a proposito, che le pitture che egli poi sopra vi fece, si sono insino a questo giorno conservate. E meglio starebbono se la stracurataggine di chi ne doveva aver cura, non l’avesse lasciate molto offendere dall’umido; perché il non avere a ciò, come si poteva agevolmente, proveduto è stato cagione, che avendo quelle pitture patito umido, si sono guaste in certi luoghi, e l’incarnazioni fatte nere, e l’intonaco scortecciato; senzaché la natura del gesso, quando è con la calcina mescolato, è d’infracidare col tempo e corrompersi; onde nasce che poi per forza guasta i colori, sebben pare che da principio faccia gran presa, e buona.

Sono in queste storie, oltre al ritratto di M. Farinata degl’Uberti, molte belle figure, e massimamente certi villani, i quali nel portare le dolorose nuove a Iobbe, non potrebbono essere più sensati, ne meglio mostrare il dolore che avevano per i perduti bestiami e per l’altre disaventure, di quello, che fanno. Parimente ha grazia stupenda la figura d’un servo, che con una rosta sta intorno a Iobbe piagato, e quasi abbandonato da ognuno: E come, che ben fatto sia in tutte le parti, è maraviglioso nell’attitudine che fa, cacciando con una delle mani le mosche al lebroso padrone, e puzzolente, e con l’altra tutto schifo turandosi il naso, per non sentire il puzzo. Sono similmente l’altre figure di queste storie e le teste, così de’ Maschi come delle femmine, molto belle et i panni in modo lavorati morbidamente, che non è maraviglia se quell’opera gl’acquistò in quella Città e fuori tanta fama, che papa Benedetto IX da Trevisi, mandasse in Toscana un suo cortigiano a vedere, che uomo fusse Giotto, e quali fussero l’opere sue, avendo disegnato far in S. Piero alcune pitture.” (1:123)

Translation

“This panel [= the Louvre Pala, showing the stigmatization of St Francis], which today is seen in San Francesco in Pisa on a pillar beside of the high-altar, and is held in great veneration as a memorial of so great a man, was the reason that the Pisans, having just finished the building of the Campo Santo after the design of Giovanni, son of Niccola Pisano, as has been said above, gave to Giotto the painting of part of the inner walls, to the end that, since this so great fabric was all encrusted on the outer side with marbles and with carvings made at very great cost, and roofed over with lead, and also full of sarcophagi and ancient tombs once belonging to the heathens and brought to Pisa from various parts of the world, even so it might be adorned within, on the walls, with the noblest painting. Having gone to Pisa, then, for this purpose, Giotto made in fresco, on the first part of the wall in that Campo Santo, six large stories of the most patient Job. And because he judiciously reflected that the marbles of that part of the building where he had to work were turned towards the sea, and that, all being saline marbles, they are ever damp by reason of the south-east winds and throw out a certain salt moisture, even as the bricks of Pisa do for the most part, and that therefore the colours and the paintings fade and corrode. So to preserve his work as long as possible, wherever he intended to paint in fresco he first laid on an undercoat, or what we would call an intonaco or plaster, made of chalk, gypsum, and powdered brick. This technique was so successful that the paintings he did have survived to the present day. They would be in even better condition, as a matter of fact, if they had not been considerably damaged by damp because of the neglect of those who were in charge of them. No precautions were taken (although it would have been a simple matter to have done so) and as a result the paintings which survived the damp were ruined in several places, the flesh tints having darkened and the plaster flaked off. In any case when gypsum is mixed with chalk it always deteriorates and decays, so although when it is used it appears to make an excellent and secure binding, the colours inevitably spoilt.

In these scenes, besides the portrait of Messer Farinata degli Uberti [ca. 1212-1264, a military leader of the Ghibelline faction in Florence, who successfully lead the Ghibelline forces at the Battle of Montaperti in 1260], there are many beautiful figures, and above all certain villagers, who, in carrying the grievous news to Job, could not be more full of feeling nor show better than they do the grief that they felt over the lost cattle and over the other misadventures. Likewise there is amazing grace in the figure of a man-servant who is standing with a fan beside Job, who is covered with ulcers and almost abandoned by all; and although he is well done in every part, he is marvellous in the attitude that he strikes in chasing the flies from his leprous and stinking master with one hand, while with the other he is holding his nose in disgust, in order not to notice the stench. In like manner, the other figures in these scenes and the heads both of the males and of the women are very beautiful; and the draperies are wrought to such a degree of softness that it is no marvel if this work acquired for him so great fame both in that city and abroad, that Pope Benedict IX of Treviso sent one of his courtiers into Tuscany to see what sort of man was Giotto, and of what kind his works, having designes to have some pictures made in S. Pietro.” (vol. 1, pp. 76-78)

Transcription

“Fu in modo Eccellente Stefano pittore Fiorentino, e discepolo di Giotto, che non pure superò tutti gl’altri, che inanzi a lui si erano affaticati nell’arte, ma avanzò di tanto il suo Maestro stesso, che fu, e meritamente, tenuto il miglior di quàli pittori erano stati in fino a quel tempo, come chiaramente dimostrano l’opere sue. Dipinse costui in fresco la N. Donna del Campo Santo di Pisa, che è alquanto meglio di disegno e di colorito che l’opera di Giotto: E in Fiorenza nel chiostro di S. Spirito, tre archetti a fresco.” (1:140)

Translation

“Stefano painter of Florence and disciple of Giotto, was so excellent, that he not only surpassed all the others who had labored in the art before him, but outstripped his own master himself by so much that he was held, and deservedly, the best of all the painters who had lived up to that time, as his works clearly demonstrate. He painted in fresco the Madonna of the Campo Santo in Pisa, which is no little better in design and in coloring than the work of Giotto; and in Florence, in the cloister of S. Spirito, he painted three little arches in fresco.” (vol. 1, p. 109)

4. Vita di Pietro Laurati Pittore Sanese

Transcription

“Da Fiorenza andato a Pisa, lavorò in Campo Santo, nella facciata, che è accanto alla porta principale, tutta la vita de’ santi padri, con si vivi affetti, e con sì belle attitudini, che, paragonando Giotto, ne riportò grandissima lode: havendo espresso in alcune teste col disegno, e con i colori tutta quella vivacità, che poteva mostrare la maniera di que’ tempi. Da Pisa trasferitosi a Pistoia, fece in san Francesco in una tavola a tempera una Nostra Donna, con alcuni Angeli intorno molto bene accommodati. (1:145)

Translation

“Going from Florence to Pisa, he wrought in the Campo Santo, on the wall that is beside the principal door, all the lives of the Holy Fathers, with expressions so lively and attitudes so beautiful that he equaled Giotto and gained thereby very great praise, having expressed in certain heads, both with drawing and with color, all that vivacity that the manner of those times was able to show. From Pisa he went to Pistoia, where he made a Madonna with some angels round her, very well grouped, on a panel in distemper, for the Church of San Francesco.” (vol. 1, 117-118)

Transcription

“Essendo non molto dopo queste cose condotto Buonamico a Pisa, dipinse nella Badia di san Paolo a Ripa d’Arno allora de’ monaci di Vallombrosa, in tutta la crociera di quella chiesa da tre bande, e dal tetto insino in terra, molte storie del Testamento Vecchio, cominciando dalla creazione dell’huomo, e siguitando insino a tutta la edificazione della torre di Nebroth […]. Fu compagno in questa opera di Buonamico, Bruno di Giovanni pittore, che cosi è chiamato in sul vecchio libro della compagnia; il quale Bruno, celebrato anch’egli, come piacevole huomo dal Boccaccio, finite le dette storie delle facciate, dipinse nella medesima Chiesa l’altar di santa Orsola con la compagnia delle Vergini. […] Ma perché nel fare questa opera Bruno si doleva, che le figure, che in essa faceva, non havevano il vivo, come quelle di Buonamico: Buonamico come burlevole per insegnargli a fare le figure, non pur vivaci, ma che favellassono, gli fece far alcune parole, che uscivano di bocca a quella femina che si raccomanda alla santa: e in risposta della santa a lei; havendo ciò visto Buonamico nell’opere, che haveva fatte nella medesima città Cimabue. La qual cosa, come piacque a Bruno, e agl’altri huomini sciocchi di quei tempi; così piace ancor oggi a certi goffi, che in ciò sono serviti da artefici plebei, come essi sono. E di vero pare gran fatto, che da questo principio sia passata in uso una cosa, che per burla, e non per altro fu fatta fare; conciosia, che anco una gran parte del Camposanto, fatta da lodati maestri sia piena di questa gofferia.

L’opere, dunque, di Buonamico, essendo molto piaciute ai Pisani, gli fu fatto fare dall’Operaio di Camposanto quattro storie in fresco, dal principio del mondo insino alla fabbrica dell’arca di Noè et intorno alle storie un ornamento, nel quale fece il suo ritratto di naturale, cioè in un fregio, nel mezzo del quale e in su le quadrature sono alcune teste, fra le quali, come ho detto, si vede la sua, con un capuccio, come apunto stà quello, che di sopra si vede. E perché in questa opera è un Dio, che con le braccia tiene i cieli, e gl’elementi, anzi la machina tutta dell’universo, Buonamico per dichiarare la sua storia con versi simili alle pitture di quell’età, scrisse a’ piedi in lettere maiuscole di sua mano, come si può anco vedere, questo sonetto, il quale per l’antichità sua e per la semplicità del dire di que’ tempi, mi è paruto di mettere in questo luogo, come che forse, per mio avviso, non sia per molto piacere, se non se forse come cosa che fa fede di quanto sapevano gli huomini di quel secolo:

Voi che avvisate questa dipintura / Di Dio pietoso, sommo creatore / lo qual fé tutte cose con amore / pesate, numerate et in misura. / In nove gradi Angelica Natura / in nello empirio ciel pien di splendore / Colui, che non si muove, ed è motore / ciascuna cosa fece buona, e pura. / Levate gl’occhi del vostro intelletto / Considerate quanto è ordinato / Lo mondo universale, e con affetto / Lodate lui che l’ha sì ben creato / Pensate di passare a tal diletto / Tra gl’Angeli, dove è ciascun beato. / Per questo mondo si vede la gloria / Lo basso, et il mezo, e l’alto in questa storia.

Et per dire il vero, fu grand’animo quello di Buonamico a mettersi a far un Dio Padre grande cinque braccia, le gierarchie, i cieli, gl’ angeli, il zodiaco e tutte le cose superiori insino al cielo della Luna. E poi l’elemento del fuoco, l’aria, la terra e finalmente il centro. E per riempire i due angoli da basso fece in uno, S. Agostino e nell’altro S. Tommaso d’Aquino. Dipinse, nel medesimo Camposanto Buonamico in testa dove è hoggi di marmo la sepoltura del Corte, tutta la passione di Christo, con gran numero di figure a piedi et a cavallo, e tutte in varie, e belle attitudini; e seguitando la storia, fece la resurrezzione e l’apparire di Christo a gl’Apostoli, assai acconciamente.” (1:159-161)

Translation

Being summoned to Pisa no long time after these events, Buonamico painted many stories of the Old Testament in the Abbey of S. Paolo a Ripa d’Arno, then belonging to the monks of Vallombrosa, in both transepts of the church, on three sides, and from the roof down to the floor, beginning with the Creation of man, and continuing up to the completion of the Tower of Nimrod. […] A companion of Buffalmacco in this work was Bruno di Giovanni, a painter, who is thus called in the old book of the Company, which Bruno (also celebrated as a gay fellow by Boccaccio), the said scenes on the walls being finished, painted the altar of S. Ursula with the company of virgins, in the same church. […] Now, for the reason that in painting this work Bruno was bewailing that the figures which he was making therein had not the same life as those of Buonamico, the latter, in his waggish way, in order to teach him to make his figures not merely vivacious but actually speaking, made him paint some words issuing from the mouth of that woman who is supplicating the Saint, and the answer of the Saint to her, a device that Buonamico had seen in the works that had been made in the same city by Cimabue. This expedient, even as it pleased Bruno and the other thick-witted men of those times, in like manner pleases certain boors today, who are served therein by craftsmen as vulgar as themselves. And in truth it seems extraordinary that from this beginning there should have passed into use a device that was employed for a jest and for no other reason, insomuch that even a great part of the Campo Santo, wrought by masters of repute, is full of this rubbish.

The works of Buonamico, then, finding much favor with the Pisans, he was charged by the Warden of the Works of the Campo Santo to make four scenes in fresco, from the beginning of the world up to the construction of Noah’s Ark, and round the scenes an ornamental border, wherein he made his own portrait from the life namely, in a frieze, in the middle of which, and on the corners, are some heads, among which, as I have said, is seen his own, with a cap exactly like the one that is seen above. And because in this work there is a God, who is upholding with his arms the heavens and the elements nay, the whole body of the universe Buonamico, in order to explain his story with verses similar to the pictures of that age, wrote this sonnet in capital letters at the foot, with his own hand, as may still be seen; which sonnet, by reason of its antiquity and of the simplicity of the language of those times, it has seemed good to me to include in this place, although in my opinion it is not likely to give much pleasure, save perchance as something that bears witness as to what was the knowledge of the men of that century:

You who behold this painting / of the pious God, highest creator, / who made all things with love, / weighted, numbered and measured. / In nine grades the angelic nature / In the empyreum the heaven full of splendor / He who is unmoved mover / made everything good and pure / raise your mind’s eyes / consider how ordered the universe is, / and with affection / praise Him who created them so well / Think how you can arrive at such pleasure / between the angels where everyone is blessed / Through this world the glory can be seen / the bottom, the middle and the top in this painting.

And to tell the truth, it was very courageous in Buonamico to undertake to make a God the Father five braccia high, with the hierarchies, the heavens, the angels, the zodiac, and all the things above, even to the heavenly body of the moon, and then the element of fire, the air, the earth, and finally the nether regions; and to fill up the two angles below he made in one, S. Augustine, and in the other, S. Thomas Aquinas. At the head of the same Campo Santo, where there is now the marble tomb of Corte, Buonamico painted the whole Passion of Christ, with a great number of figures on foot and on horseback, and all in varied and beautiful attitudes; and continuing the story he made the Resurrection and the Apparition of Christ to the Apostles, passing well. Having finished these works and at the same time all that he had gained Pisa, which was not little, he returned to Florence as poor as he had left it, and there he made many panels and works in fresco, whereof there is no need to make further record.” (vol. 1, pp. 144-147)

6. Vita di Simone Sanese Pittore

Transcription

“Lavorò poi Simone tre facciate del capitolo della detta S. M. Nouella molto felicemente. […] Conciòsia, che pigliando le facciate intere, con diligentissima osservazione fa in ciascuna diverse storie su per un monte, e non divide con ornamenti tra storia e storia, come usarono di fare i vecchi, e molti moderni, che fanno la terra sopra l’aria quattro, o cinque volte, come è la capella maggiore di questa medesima chiesa et il Camposanto di Pisa; dove, dipignendo molte cose a fresco, gli fu forza far contra sua voglia cotali divisioni, havendo gl’altri pittori, che havevano in quel luogo lavorato, come Giotto, e Buonamico suo maestro, cominciato a fare le storie loro con questo malo ordine.

Seguitando dunque in quel Campo Santo, per meno error il modo tenuto dagli altri, fece Simone sopra la porta principale, di dentro, una nostra Donna in fresco, portata in cielo da un coro d’Angeli, che cantano, e suonano tanto vivamente, che in loro si conoscono tutti que’varii effetti, che i musici, cantando, o sonando fare sogliono; come è porgere l’orecchio al suono, aprir la bocca in diversi modi, alzar gl’occhi al cielo, gonfiar le guance, ingrossar la gola et insomma tutti gl’altri atti, e movimenti che si fanno nella musica. Sotto questa assunta in tre quadri fece alcune storie della vita di S. Ranieri Pisano; nella prima, quando giovanetto, sonando il salterio, fa ballar alcune fanciulle, bellissime per l’arie de’ volti, e per l’ornamento degl’habiti et acconciature di que’ tempi. Vedesi poi lo stesso Ranieri, essendo stato ripreso di cotale lascivia dal beato Alberto Romito, starsi col volto chino, e lagrimoso e con gl’occhi fatti rossi dal pianto, tutto pentito del suo peccato, mentre Dio in aria, circondato da un celeste lume, fa sembiante di perdonargli. Nel secondo quadro è quando Ranieri, dispensando le sue facultà ai poveri di Dio, per poi montar in barca, ha intorno una turba di poveri, di storpiati, di donne e di putti, molto affettuosi nel farsi innanzi, nel chiedere, e nel ringraziarlo. E nello stesso quadro è ancora, quando questo Santo, ricevuta nel tempio la schiavina da pellegrino, sta dinanzi a Nostra Donna, che circondata da molti Angeli, gli mostra che si riposerà nel suo grembo in Pisa, le quali tutte figure hanno vivezza e bell’aria nelle teste. Nella terza è dipinto da Simone quando, tornato dopo sette anni d’oltra mare, mostra haver fatto tre quarantane in terra santa, e che standosi in coro a udir i divini uffizii dove molti putti cantano, è tentato dal Demonio, il quale si vede scacciato da un fermo proponimento, che si scorge in Ranieri di non voler offender Dio, aiutato da una figura, fatta da Simone per la constanza, che fa partir l’antico Avversario, non solo tutto confuso, ma con bella invenzione e capricciosa, tutto pauroso, tenendosi nel fuggire le mani al capo e caminando con la fronte bassa, e stretto nelle spalle a più potere, e dicendo, come se gli vede scritto uscire di bocca: Io non posso più. E finalmente in questo quadro è ancora quando Ranieri, in sul monte Tabor ingenocchiato, vede miracolosamente Christo in aria con Moise et Elia. Le quali tutte cose di quest’opera et altre, che si tacciono, mostrano, che Simone fu molto capriccioso et intese il buon modo di comporre leggiadramente le figure nella maniera di que’ tempi.” (1:171-173)

Translation

“Next, Simone painted three walls of the Chapterhouse of the said S. Maria Novella, very happily. […] Taking up the whole walls, with very diligent judgment he made in each wall diverse scenes on the slope of a mountain, and did not divide scene from scene with ornamental borders, as the old painters were wont to do, and many moderns, who put the earth over the sky four or five times, as it is seen in the principal chapel of this same church, and in the Campo Santo of Pisa, where, painting many works in fresco, he was forced against his will to make such divisions, for the other painters who had worked in that place, such as Giotto and Buonamico his master, had begun to make their scenes with this bad arrangement.

In that Campo Santo, then, following as the lesser evil the method used by the others, Simone made in fresco, over the principal door and on the inner side, a Madonna borne to Heaven by a choir of angels, who are singing and playing so vividly that there are seen in them all those various gestures that musicians are wont to make in singing or playing, such as turning the ears to the sound, opening the mouth in diverse ways, raising the eyes to Heaven, blowing out the cheeks, swelling the throat, and in short all the other actions and movements that are made in music. Under this Assumption, in three pictures, he made some scenes from the life of S. Ranieri of Pisa. In the first scene he is shown as a youth, playing the psaltery and making some girls dance, who are most beautiful by reason of the air of the heads and of the loveliness of the costumes and head-dresses of those times. Next, the same Ranieri, having been reproved for such lasciviousness by the Blessed Alberto the Hermit, is seen standing with his face downcast and tearful and with his eyes red from weeping, all penitent for his sin, while God, in the sky, surrounded by a celestial light, appears to be pardoning him. In the second picture Ranieri, distributing his wealth to God’s poor before mounting on board ship, has round him a crowd of beggars, of cripples, of women, and of children, all most touching in their pushing forward, their entreating, and their thanking him. And in the same picture, also, that Saint, having received in the Temple the gown of a pilgrim, is standing before a Madonna, who, surrounded by many angels, is showing him that he will repose on her bosom in Pisa; and all these figures have vivacity and a beautiful air in the heads. In the third Simone painted the scene when, having returned after seven years from beyond the seas, he is showing that he has spent thrice forty days in the Holy Land, and when, standing in the choir to hear the Divine offices, he is tempted by the Devil, who is seen driven away by a firm determination that is perceived in Ranieri not to consent to offend God, assisted by a figure made by Simone to represent Constancy, who is chasing away the ancient adversary not only all in confusion but also (with beautiful and fanciful invention) all in terror, holding his hands to his head in his flight, and walking with his face downcast and his shoulders shrunk as close together as could be, and saying, as it is seen from the writing that is issuing from his mouth: “I can no more.” And finally, there is also in this picture the scene when Ranieri, kneeling on Mount Tabor, is miraculously seeing Christ in air with Moses and Elias; and all the features of this work, with others that are not mentioned, show that Simone was very fanciful and understood the good method of grouping figures gracefully in the manner of those times. These scenes finished, he made two panels in distemper in the same city, assisted by Lippo Memmi, his brother, who had also assisted him to paint the Chapterhouse of S. Maria Novella and other works.” (vol. 1, pp. 170-172)

7. Vita di Andrea di Cione Orgagna Pittore, Scultore, et Architetto Fiorentino

Transcription

“Mossi dalla fama di quest’opre dell’Orgagna, che furono molto lodate, coloro che in quel tempo governavano Pisa, lo fecero condurre a lavorare nel Campo Santo di quella Città, un pezzo d’una facciata, secondo, che prima Giotto e Buffalmacco fatto havevano. Onde messovi mano, in quella dipinse Andrea un Giudizio Universale con alcune fantasie à suo capriccio, nella facciata di verso il Duomo, allato alla Passione di Christo fatta da Buffalmacco, dove nel canto facendo la prima storia, figurò in essa tutti i gradi de’ Signori Temporali, involti nei piaceri di questo mondo; ponendogli a sedere sopra un prato fiorito, e sotto l’ombra di molti melaranci, che facendo amenissimo bosco, hanno sopra i rami alcuni amori, che volando a torno, e sopra molte giovani Donne, ritratte tutte, secondo, che si vede, dal Naturale di femmine nobili, e signore di que’ tempi le quali per la lunghezza del tempo non si riconoscono, fanno sembiante di saettare i cuori di quelle alle quali sono giovani uomini appresso, e signori che stanno a udir’ suoni, e canti, e a vedere amorosi balli di garzoni, e Donne che godano con dolcezza i loro amori.

Fra’ quali signori ritrasse l’Orgagna Castruccio, signor di Lucca, e giovane di bellissimo aspetto, con un Cappuccio azzurro avvolto intorno al capo e con uno sparviere in pugno, e appresso lui altri signori di quell’età, che non si sa chi sieno. Insomma fece con molta diligenza in questa prima parte, per quanto capiva il luogo, e richiedeva l’arte, tutti i diletti del mondo graziosissimamente. Dall’altra parte nella medesima storia, figurò sopra un’alto monte la vita di coloro che, tirati dal pentimento, de’ peccati, e dal disiderio d’esser salvi, sono fuggiti dal mondo à quel Monte tutto pieno di Santi Romiti, che servono al Signore diverse cose operando con vivacissimi affetti. Alcuni leggendo et orando si mostrano tutti intenti alla contemplativa, e altri lavorando per guadagnare il vivere, nell’attiva variamente si essercitano.

Vi si vede fra gl’altri un Romito, che mugne una Capra, il quale non può essere più pronto né più vivo in figura di quello che gli è. E poi da basso San Machario, che mostra a que’ tre Re, che cavalcando con loro donne e brigata vanno a caccia, la miseria humana in tre Re, che morti e non del tutto consumati, giaceno in una sepoltura, con attenzione guardata dai Re vivi, in diverse, e belle attitudini piene d’amirazione, e pare quasi che considerino con pietà di se stessi. d’havere in breve a divenire tali. In un di questi Re a cavallo ritrasse Andrea Uguccione della Faggiuola Aretino, in una figura che si tura con una mano il naso, per non sentire il puzzo de’ Re morti e corrotti. Nel mezzo di questa storia è la morte che volando per Aria, vestita di nero, fa segno d’havere con la sua falce levato la vita a molti, che sono per terra d’ogni stato e condizione, poveri, ricchi, storpiati, ben disposti, giovani, vecchi, maschi, femmine, e insomma d’ogni età, e sesso buon numero. E perché sapeva che ai Pisani, piaceva l’invenzione di Buffalmacco, che fece parlare le figure di Bruno in San Paulo a Ripa d’Arno, facendo loro uscire di bocca alcune lettere, empié l’Orgagna tutta quella sua opera di cotali scritti de’ quali la maggior parte, essendo consumati dal tempo, non s’intendono. A certi vecchi dunque storpiati fa dire:

Da che prosperitade ci ha lasciati / O morte, medicina d’ogni pena / Deh, vieni a darne homai l’ultima cena.

Con altre parole, che non s’intendono, e versi cosi all’antica composti, secondo, che ho ritratto, dall’Orgagna medesimo, che attese alla poesia, e a fare qualche sonetto. Sono intorno a que’ corpi morti alcuni Diavoli che cavano loro di bocca l’anime, e le portano a certe bocche piene di fuoco, che sono sopra la sommità d’un altissimo monte; di contro a questi sono Angeli, che similmente a altri di que’ morti, che vengono a essere de’ buoni, cavano l’anime di bocca, e le portano volando in Paradiso. Et in questa storia è una scritta grande, tenuta da due Angeli, dove sono queste parole:

Ischermo di savere e di ricchezza / Di nobiltate ancora, e di prodezza / vale niente ai colpi di Costei,

con alcune altre parole, che malamente s’intendono. Di sotto poi, nell’ornamento di questa storia, sono Nove Angeli, che tengono in alcune accomodate scritte, Motti volgari e latini, posti in quel luogo da basso, perché in alto guastavano la storia, e il non gli porre nell’opera, pareva mal fatto all’Auttore, che gli reputava bellissimi, e forse erano ai gusti di quell’età. Da noi si lasciano la maggior parte per non fastidire altrui con simili cose impertinenti e poco dilettevoli, senza che essendo il più di cotali brevi cancellati, il rimanente viene a restare poco meno che imperfetto. Facendo dopo queste cose l’Orgagna il giudizio, collocò Gesù Christo in alto sopra le nuvole in mezzo ai dodici suoi Apostoli, giudicare i vivi, e i morti, mostrando con bell’arte, e molto vivamente, da un lato i dolorosi affetti de’ Dannati, che piangendo, sono da furiosi Demonij strascinati all’inferno. E dall’altro la letizia, e il Giubilo de’ buoni, che da una squadra d’Angeli guidati da Michele Arcangelo, sono, come eletti, tutti festosi tirati alla parte destra de’ beati. Et è un peccato veramente, che per mancamento di scrittori, in tanta moltitudine d’huomini togati, Cavallieri, e altri signori, che vi sono effigiati e ritratti dal Naturale, come si vede di nessuno, o di pochissimi, si sappiano i nomi, ò chi furono. Ben si dice, che un papa, che vi si vede, è Innocentio Quarto, amico di Manfredi.

Dopo quest’opera et alcune sculture di marmo fatte con suo molto onore nella Madonna, ch’è in su la coscia del ponte vecchio, lasciando Bernardo suo fratello a lavorare in Campo Santo, da per se un’Inferno, secondo, che, è descritto da Dante, che fu poi l’anno 1530 guasto e racconcio dal Sollazzino, pittore de’ tempi nostri, se ne tornò Andrea a Fiorenza, dove nel mezzo della chiesa di Santa Croce a man destra, in una grandissima facciata, dipinse a fresco le medesime cose che dipinse nel Campo Santo di Pisa, in tre quadri simili, eccetto però la storia dove San Macario mostra a’ tre Re la miseria humana; e la vita de’ romiti, che servono a Dio in su quel monte.” (1:182-184)

Translation

“Moved by the fame of these works of Orcagna, which were much praised, the men who at that time were governing Pisa had him summoned to work on a portion of one wall in the Campo Santo of that city, even as Giotto and Buffalmacco had done before. Wherefore, putting his hand to this, Andrea painted a Universal Judgment, with some fanciful inventions of his own, on the wall facing towards the Duomo, beside the Passion of Christ made by Buffalmacco; and making the first scene on the corner, he represented therein all the degrees of lords temporal wrapped in the pleasures of this world, placing them seated in a flowery meadow and under the shade of many orange-trees, which make a most delicious grove and have some Cupids in their branches above; and these Cupids, flying round and over many young women (all portraits from the life, as it seems clear, of noble ladies and dames of those times, who, by reason of the long lapse of time, are not recognized), are making a show of shooting at the hearts of these young women, who have beside them young men and nobles who are standing listening to music and song and watching the amorous dances of youths and maidens, who are sweetly taking joy in their loves.

Among these nobles Orcagna portrayed Castruccio, Lord of Lucca, as a youth of most beautiful aspect, with a blue cap wound round his head and with a hawk on his wrist, and near him other nobles of that age, of whom we know not who they are. In short, in that first part, in so far as the space permitted and his art demanded, he painted all the delights of the world with exceeding great grace. In the other part of the same scene he represented on a high mountain the life of those who, drawn by repentance for their sins and by the desire to be saved, have fled from the world to that mountain, which is all full of saintly hermits who are serving the Lord, busy in diverse pursuits with most vivacious expressions. Some, reading and praying, are shown all intent on contemplation, and others, laboring in order to gain their livelihood, are exercising themselves in various forms of action.

There is seen here among others a hermit who is milking a goat, who could not be more active or more lifelike in appearance than he is. Below there is S. Macarius showing to three Kings, who are riding with their ladies and their retinue and going to the chase, human misery in the form of three Kings who are lying dead but not wholly corrupted in a tomb, which is being contemplated with attention by the living Kings in diverse and beautiful attitudes full of wonder, and it appears as if they are reflecting with pity for their own selves that they have in a short time to become such. In one of these Kings on horseback Andrea portrayed Uguccione della Faggiuola of Arezzo, in a figure which is holding its nose with one hand in order not to feel the stench of the dead and corrupted Kings. In the middle of this scene is Death, who, flying through the air and draped in black, is showing that she has cut off with her scythe the lives of many, who are lying on the ground, of all sorts and conditions, poor and rich, halt and whole, young and old, male and female, and in short a good number of every age and sex. And because he knew that the people of Pisa took pleasure in the invention of Buffalmacco, who gave speech to the figures of Bruno in S. Paolo a Ripa d’Arno, making some letters issue from their mouths, Orcagna filled this whole work of his with such writings, whereof the greater part, being eaten away by time, cannot be understood. To certain old men, then, he gives these words:

Because prosperity has left us / Death, cure for every pain, / Come and give us the last supper!

with other words that cannot be understood, and verses likewise in ancient manner, composed, as I have discovered, by Orcagna himself, who gave attention to poetry and to making a sonnet or two. Round these dead bodies are some devils who are tearing their souls from their mouths, and are carrying them to certain pits full of fire, which are on the summit of a very high mountain. Over against these are angels who are likewise taking the souls from the mouths of others of these dead people, who have belonged to the good, and are flying with them to Paradise. And in this scene there is a scroll, held by two angels, wherein are these words:

Shields of knowledge and richness / Nobility and also gentleness / They are not able to parry her blows

with some other words that are difficult to understand. Next, below this, in the border of this scene, are nine angels who are holding legends both Italian and Latin in some suitable scrolls, put into that place below because above they were like to spoil the scene, and not to include them in the work seemed wrong to their author, who considered them very beautiful; and it may be that they were to the taste of that age. The greater part is omitted by us, in order not to weary others with such things, which are not pertinent and little pleasing, not to mention that the greater part of these inscriptions being effaced, the remainder is little less than fragmentary. After these works, in making the Judgment, Orcagna set Jesus Christ on high above the clouds in the midst of His twelve Apostles, judging the quick and the dead; showing on one side, with beautiful art and very vividly, the sorrowful expressions of the damned who are being dragged weeping by furious demons to Hell, and, on the other, the joy and the jubilation of the good, whom a body of angels guided by the Archangel Michael are leading as the elect, all rejoicing, to the right, where are the blessed. And it is truly a pity that for lack of writers, in so great a multitude of men of the robe, chevaliers, and other lords, that are clearly depicted and portrayed there from the life, there should be not one, or only very few, of whom we know the names or who they were; although it is said that a Pope who is seen there is Innocent IV, friend of Manfredi.

After this work, and after making some sculptures in marble for the Madonna that is on the abutment of the Ponte Vecchio, with great honour for himself, he left his brother Bernardo to execute by himself a Hell in the Campo Santo, which is described by Dante, and which was afterwards spoilt in the year 1530 and restored by Sollazzino, a painter of our own times ; and he returned to Florence, where, in the middle of the Church of S. Croce, on a very great wall on the right, he painted in fresco the same subjects that he painted in the Campo Santo of Pisa, in three similar pictures, excepting, however, the scene where S. Macarius is showing to three Kings the misery of man, and the life of the hermits who are serving God on that mountain.” (vol. 1, pp. 190-193)

8. Vita di Antonio Viniziano Pittore

Transcription

“Essendo, dopo quest’opere, Antonio condotto a Pisa dallo Operaio di Campo Santo, seguitò di fare in esso le storie del beato Ranieri, huomo santo di quella città, già cominciate da Simone sanese, pur coll’ordine di lui. Nella prima parte della quale opera fatta da Antonio, si vede in compagnia del detto Ranieri, quando imbarca per tornare a Pisa, buon numero di figure lavorate con diligenza, fra le quali è il ritratto del conte Gaddo, morto dieci anni innanzi, e di Neri suo zio stato signor di Pisa; fra le dette figure, è ancor molto notabile quella d’uno spiritato, perché, avendo viso di pazzo, i gesti della persona stravolti, gl’hocchi stralucenti e la bocca che digrignando mostra i denti, somiglia tanto uno spiritato da dovero, che non si può immaginare né più viva pittura né più somigliante al Naturale.

Nell’altra parte, che è allato alla sopra detta, tre figure che si maravigliano, vedendo che il beato Ranieri mostra il diavolo in forma di gatto sopr’una botte a un’hoste grasso che ha aria di buon compagno e che tutto timido si raccomanda al Santo, si possono dire veramente bellissime, essendo molto ben condotte nell’attitudini, nella maniera de’ panni, nella varietà delle teste et in tutte l’altre parti. Non lungi, le donne dell’hoste anch’elleno non potrebbono essere fatte con più grazia havendole fatte Antonio con certi habiti spediti, e con certi modi tanto proprij di donne che stiano per servigio d’hosterie, che non si può immaginare meglio. Né può più piacere di quello che faccia l’historia parimente, dove i canonici del Duomo di Pisa, in habiti bellissimi di que’ tempi et assai diversi da quegli che s’usano oggi e molto graziati, ricevono a mensa s. Ranieri, essendo tutte le figure fatte con molta considerazione. Dove poi è dipinta la morte di detto Santo, è molto bene espresso non solamente l’effetto del piangere, ma l’andare similmente di certi Angeli, che portano l’anima di lui in cielo, circondati da una luce splendidissima, e fatta con bella invenzione. E veramente non può anche, se non maravigliarsi, chi vede, nel portarsi dal clero il corpo di quel santo al Duomo, certi preti che cantano, perché nei gesti, negl’atti della persona et in tutti i movimenti facendo diverse voci, somigliano con maravigliosa proprietà un Coro di cantori. Et in questa storia è, secondo che si dice, il ritratto del Bavero.

Parimente i miracoli che fece Ranieri nell’esser portato alla sepoltura, e quelli che in un altro luogo fa essendo già in quella collocato nel Duomo, furono con grandissima diligenza dipinti da Antonio, che vi fece ciechi che ricevono la luce, rattratti che rihanno la disposizione delle membra, oppressi dal Demonio, che sono liberati, et altri miracoli espressi molto vivamente. Ma fra tutte l’altre figure merita con maraviglia essere considerato un hidropico, perciò che col viso secco, con le labbra asciutte e col corpo enfiato e tale che non potrebbe più di quello che fa questa pittura mostrare un vivo la grandissima sete degl’idropici e gl’altri effetti di quel male. Fu anche cosa mirabile in que’ tempi una Nave che egli fece in quest’opera, la quale, essendo travagliata dalla fortuna, fu da quel Santo liberata, avendo in essa fatto prontissime tutte l’azzioni de’ marinari e tutto quello che in cotali accidenti e travagli suol avvenire. Alcuni gettano, senza pensarvi, all’ingordissimo mare le care merci con tanti sudori fatigate, altri corre a provedere il legno, che sdruce, et insomma altri a altri uffizii marinareschi, che tutti sarei troppo lungo a raccontare; basta, che tutti sono fatti con tanta vivezza e bel modo ch’è una maraviglia.

In questo medesimo luogo, sotto la vita de’ Santi padri dipinta da Pietro Laurati sanese fece Antonio il corpo del beato Oliverio, insieme con l’abate Panuzio e molte cose della vita loro, in una cassa figurata di marmo, la qual figura è molto ben dipinta. Insomma tutte quest’opere che Antonio fece in Camposanto sono tali che universalmente et a gran ragione sono tenute le migliori di tutte quelle che da molti Eccellenti maestri sono state in più tempi in quel luogo lavorate; perciò che, oltre i particolari detti, egli lavorando ogni cosa a fresco e non mai ritoccando alcuna cosa a secco fu cagione che insino a hoggi si sono in modo mantenute vive nei colori, ch’elle possono, ammaestrando quegli dell’arte, far loro conoscere quanto il ritoccare le cose fatte a fresco poiché sono secche con altri colori, porti, come si è detto nelle Teoriche, nocumento alle pitture et ai lavori, essendo cosa certissima, che gl’invecchia, e non lascia purgargli dal tempo l’esser coperti di colori che hanno altro corpo, essendo temperati con gomme, con draganti, con uova, con colla o altra somigliante cosa, che appanna quel di sotto e non lascia, che il corso del tempo e l’aria purghi quello che è veramente lavorato a fresco sulla calcina molle, come avverrebbe se non fussero loro sopraposti altri colori a seccho.

Avendo Antonio finita quest’opera che, come degna in verità d’ogni lode gli fu onoratamente pagata da’ Pisani che poi sempre molto l’amarono, se ne tornò a Firenze, dove a Nuovoli fuor della Porta al Prato, dipinse in un Tabernacolo a Giouanni degl’Agli un Christo morto, con molte figure la storia de’Magi, et il de del Giudizio molto bello.” (1:207-208)

Translation

“Antonio, being summoned after these works to Pisa by the Warden of Works of the Campo Santo, continued therein the painting of the stories of the Blessed Ranieri, a holy man of that city, formerly begun by Simone Sanese, following his arrangement. In the first part of the work painted by Antonio there is seen, in company with the said Ranieri when he is embarking in order to return to Pisa, a good number of figures wrought with diligence, among which is the portrait of Count Gaddo, who died ten years before, and that of Neri, his uncle, once Lord of Pisa. Among the said figures, also, that of a maniac is very notable, for, with the features of madness, with the person writhing in distorted gestures, the eyes blazing, and the mouth gnashing and showing the teeth, it resembles a real maniac so greatly that it is not possible to imagine either a more lifelike picture or one more true to nature.

In the next part, which is beside that named above, three figures (who are marvelling to see the Blessed Ranieri showing the Devil, in the form of a cat on a barrel, to a fat host, who has the air of a gay companion, and who, all fearful, is commending himself to the Saint) can be said to be truly very beautiful, being very well executed in the attitudes, the manner of the draperies, the variety of the heads, and all the other parts. Not far away are the host’s womenfolk, and they, too, could not be wrought with more grace, Antonio having made them with certain tucked-up garments and with certain ways so peculiar to women who serve in hostelries, that nothing better can be imagined. Nor could that scene likewise be more pleasing than it is, wherein the Canons of the Duomo of Pisa, in very beautiful vestments of those times, no little different from those that are used today and very graceful, are receiving S. Ranieri at table, all the figures being made with much consideration. Next, in the painting of the death of the said Saint, he expressed very well not only the effect of weeping, but also the movement of certain angels who are bearing his soul to Heaven, surrounded by a light most resplendent and made with beautiful invention. And truly one cannot but marvel as one sees, in the bearing of the body of that Saint by the clergy to the Duomo, certain priests who are singing, for in their gestures, in the actions of their persons, and in all their movements, as they chant diverse parts, they bear a marvellous resemblance to a choir of singers; and in that scene, so it is said, is the portrait of the Bavarian.

In like manner, the miracles that Ranieri wrought as he was borne to his tomb, and those that he wrought in another place when already laid to rest therein in the Duomo, were painted with very great diligence by Antonio, who made there blind men receiving their sight, paralytics regaining the use of their members, men possessed by the Devil being delivered, and other miracles, all represented very vividly. But among all the other figures, that of a dropsical man deserves to be considered with marvel, for the reason that, with the face withered, with the lips shrivelled, and with the body swollen, he is such that a living man could not show more than does this picture the very great thirst of the dropsical and the other effects of that malady. A wonderful thing, too, in those times, was a ship that he made in this work, which, being in travail in a tempest, was saved by that Saint; for he made therein with great vivacity all the actions of the mariners, and everything which is wont to befall in such accidents and travailings. Some are casting into the insatiable sea, without a thought, the precious merchandize won by so much sweat and labor, others are running to see to their vessel, which is breaking up, and others, finally, to other mariners’ duties, whereof it would take too long to relate the whole; it is enough to say that all are made with so great vividness and beautiful method that it is a marvel.

In the same place, below the lives of the Holy Fathers painted by Pietro Laurati of Siena, Antonio made the body of the Blessed Oliverio (together with the Abbot Panuzio, and many events of their lives), in a sarcophagus painted to look like marble; which figure is very well painted. In short, all these works that Antonio made in the Campo Santo are such that they have been universally held, and with great reason, the best of all those that have been wrought by many excellent masters at various times in that place, for the reason that, besides the particulars mentioned, the fact that he painted everything in fresco, never retouching any part on the dry, brought it about that up to our day they have remained so vivid in the coloring that they can teach the followers of that art and make them understand how greatly the retouching of works in fresco with other colours, after they are dry, causes injury to their pictures and labors, as it has been said in the treatise on Theory; for it is a very certain fact that they are aged, and not allowed to be purified by time, by being covered with colors that have a different body, being tempered with gums, with tragacanths, with eggs, with size, or some other similar substance, which tarnishes what is below, and does not allow the course of time and the air to purify that which has been truly wrought in fresco on the soft plaster, as they would have done if other colours had not been superimposed on the dry.

Having finished this work, which, being truly worthy of all praise, brought him honorable payment from the Pisans, who loved him greatly ever afterwards, Antonio returned to Florence, where, at Nuovoli without the Porta a Prato, he painted in a shrine, for Giovanni degli Agli, a Dead Christ, the story of the Magi with many figures, and a very beautiful Day of judgment.” (vol. 2, pp. 16-19)

9. Vita di Spinello Aretino Pittore Fiorentino

Transcription

“Essendo poi chiamato a Pisa, a finire in Campo Santo sotto le storie di s. Ranieri il resto, che mancava d’altre storie in un vano, che era rimasto non dipinto, per congiugnerle insieme con quelle, che aveva fatto Giotto, Simon sanese et Antonio Viniziano, fece in quel luogo a fresco sei storie di san Petito e s. Epiro. Nella prima è quando egli giovanetto è presentato dalla madre a Diocliziano imperatore, e quando è fatto Generale degl’esserciti che dovevano andare contro ai cristiani; e così quando cavalcando gl’apparve Christo, che mostrandogli una croce bianca gli comanda, che non lo perseguiti. In un’altra storia si vede l’Angelo del Signore dare a quel santo, mentre cavalca, la bandiera della fede con la Croce bianca in campo rosso, che è poi stata sempre l’arme de’ Pisani, per havere santo Epiro pregato Dio, che gli desse un segno da portare incontro agli Nimici. Si vede appresso questa un’altra storia dove appiccata fra il santo et i pagani una fiera battaglia, molti Angeli armati combattono per la vittoria di lui; nella quale Spinello fece molte cose da considerare in que’ tempi, che l’arte, non haveva ancora né forza, né alcun buon modo d’esprimere con i colori vivamente i concetti dell’animo. E ciò furono, fra le molte altre cose, che vi sono, due soldati i quali, essendosi con una delle mani presi nelle barbe, tentano con gli stocchi nudi che hanno nell’altra torsi l’uno all’altro la vita, mostrando nel volto, et in tutti i movimenti delle membra il desiderio, che ha ciascuno di rimanere vittorioso, e con fierezza d’animo essere senza paura e quanto più si può pensare coraggiosi; e così ancora fra quegli, che combattono a cavallo, è molto ben fatto un cavalliere, che con la lancia conficca in terra la testa del nimico, traboccato rovescio del cavallo tutto spaventato.

Mostra un’altra storia il medesimo santo, quando è presentato a Diocliziano imperatore, che lo essamina della fede, e poi lo fa dare ai tormenti, e metterlo in una fornace, dalla quale egli rimane libero et in sua vece abruciati i ministri che quivi sono molto pronti da tutte le bande; et insomma tutte l’altre azzioni di quel Santo in fino alla decollazione; dopo la quale è portata l’anima in cielo; et in ultimo quando sono portate d’Alessandria a Pisa l’ossa e le reliquie di san Petito; la quale tutta opera per colorito, e per invenzione è la più bella, la più finita, e la meglio condotta che facesse Spinello; la qual cosa da questo si può conoscere che, essendosi benissimo conservata, fa oggi la sua freschezza maravigliare chiunche la vede.

Finita quest’opera in campo santo, dipinse in una Capella in san Francesco, che è la seconda allato alla maggiore, molte storie di san Bartolomeo, di santo Andrea, di san Iacopo, e di san Giouanni Apostoli, e forse sarebbe stato più lungamente a lavorare in Pisa, perché in quella città erano le sue opere conosciute, eguiderdonate, ma vedendo la città tutta sollevata, e sotto sopra, per essere stato dai Lanfranchi, cittadini Pisani, morto M. Piero Gambacorti, di nuovo con tutta la famiglia, essendo gia vecchio, se ne ritornò a Fiorenza.” (1:217-218)

Translation

“He was then summoned to Pisa in order to finish, below the stories of S. Ranieri in the Campo Santo, certain stories that were lacking in a space that had remained not painted; and in order to connect them together with those that had been made by Giotto, Simone Sanese, and Antonio Viniziano, he made in that place, in fresco, six stories of S. Petito and S. Epiro. In the first is S. Epiro, as a youth, being presented by his mother to the Emperor Diocletian, and being made General of the armies that were to march against the Christians; and also Christ appearing to him as he is riding, showing him a white Cross and commanding the Saint not to persecute Him. In another story there is seen the Angel of the Lord giving to that Saint, who is riding, the banner of the Faith with the white Cross on a field of red, which has been ever since the ensign of the Pisans, by reason of S. Epiro having prayed to God that He should give him a standard to bear against His enemies. Beside this story there is seen another, wherein, a fierce battle being contested between the Saint and the pagans, many angelsin armor are combating to the end that he may be victorious. Here Spinello wrought many things worthy of consideration for those times, when the art had as yet neither strength nor any good method of expressing vividly with color the conceptions of the mind; and such, among the many other things that are there, were two soldiers, who, having gripped each other by the beard with one hand, are seeking with their naked swords, which they have in the other hand, to rob each other of life, showing in their faces and in all the movements of their members the desire that each has to come out victorious, and how fearless and fiery of soul they are, and how courageous beyond all belief. And so, too, among those who are combating on horseback, that knight is very well painted who is pinning to the ground with his lance the head of his enemy, whom he has hurled backwards from his horse, all dismayed.

Another story shows the same Saint when he is presented to the Emperor Diocletian, who examines him with regard to the Faith, and afterwards causes him to be put to the torture, and to be placed in a furnace, wherein he remains unscathed, while the ministers of torture, who are showing great readiness there on every side, are burnt in his stead. And in short, all the other actions of that Saint are there, up to his beheading, after which his soul is borne to Heaven; and, for the last, we see the bones and relics of S. Petito being borne from Alexandria to Pisa. This whole work, both in coloring and in invention, is the most beautiful, the most finished, and the best executed that Spinello made, a circumstance which can be recognized from this, that it is so well preserved as to make everyone who sees it today marvel at its freshness.

Having finished this work in the Campo Santo, he painted many stories of S. Bartholomew, S. Andrew, S. James, and S. John, the Apostles, in a chapel in S. Francesco, which is the second from the principal chapel, and perchance he would have remained longer at work in Pisa, since in that city his works were known and rewarded; but seeing the city all in confusion and uproar by reason of Messer Pietro Gambacorti having been slain by the Lanfranchi, citizens of Pisa, he returned once again with all his family, being now old, to Florence.” (vol. 2, pp. 37-38)

10. Vita di Benozzo Gozzoli Pittore Fiorentino

Transcription

“Da Roma tornato Benozzo a Firenze, se n’andò a Pisa, dove lavorò nel Cimiterio, che è allato al Duomo, detto Campo Santo, una facciata di muro lunga quanto tutto l’edifizio, facendovi storie del Testamento vecchio con grandissima invénzione. E si puo dire che questa sia veramente un opera terribilissima, veggéndosi in essa tutte le storie della Creazione del mondo distinte a giorno per giorno. Dopo l’Arca di Noe, l’innondazione del Diluvio espressa con bellissimi componimenti, et copiosità di figure. Appresso la superba edificazione della Torre di Nebrot: l’incendio di Soddoma, e dell’altre città vicine; l’Historie d’Abramo, nelle quali sono da considerare affetti bellissimi: percioché se bene non haveva Benozzo molto singular disegno nelle figure, dimostrò nondimeno l’arte efficacemente nel sacrificio d’Isaac, per havere situato in iscorto un’asino per tal maniera, che si volta per ogni banda: Il che è tenuto cosa bellissima. Segue appresso il nascere di Moise, con que’ tanti segni, e prodigi insino a che trasse il popolo suo d’Egitto, e lo cibò tanti anni nel deserto. Aggiunse a queste tutte le storie Hebree insino a Davit et Salamone suo figliuolo. E dimostrò veramente Benozzo in questo lauoro un’animo più che grande: perché dove si grande impresa havrebbe giustamente fatto paura à una legione di pittori, egli solo la fece tutta, e la condusse à perfezione. Di maniera, che havendone acquistato fama grandissima, meritò, che nel mezo dell’opera gli fusse posto questa epigramma.

Quid spectas uolucres, pisces, e monstra ferarum?/ Et virides silvas, ethereasque Domos?/ Et pueros, iuvenes, matres, canosque Parentes?/ Queis semper vivum spirat in ore decus. / Non hac tam varis finxit simulacra figuris / Natura; ingenio factibus apta suo: / Est opus artificis; / pinxit viva ora Benoxus: / O superi vivos fundite in ora sonos.

Sono in tutta questa opera sparsi infiniti ritratti di naturale, ma perché di tutti non si ha cognizione, dirò quelli solamente, che io vi ho conosciuti di importanza, e quelli, di che ho per qualche ricordo cognizione. Nella storia dunque dove la Reina Saba và a Salamone è ritratto Marsilio Ficino fra certi prelati, l’Argiropolo dottissimo greco e Battista Platina, il quale haveva prima ritratto in Roma: et egli stesso sopra un cavallo, nella figura d’un vechiotto raso con una beretta nera, che ha nella piegha una carta bianca, forse per segno, o perché hebbe volontà di scriuervi dentro il nome suo. Nella medesima città di Pisa alle monache di san Benedetto à Ripa d’Arno, dipinse tutte le storie della vita di quel santo.

[…]

Ma tornando a Benozzo, consumato finalmente dagl’anni, e dalle fatiche d’anni 78, se n’andò al vero riposo nella città di Pisa, habitando in una casetta, che in si lunga dimora vi comperata in carraia di S. Francesco. La qual casa lasciò morendo alla sua figliuoala: et con dispiacere di tutta quella città fu honoratamente sepellito in Camposanto con questo epitaffio, che ancora si legge.

Hic tumulus est Benoti Florentini qui proxime has pinxit historias. hunc sibi Pisanor.

donavit humanitas MccccLxxviii.” (2:407-09)

Translation

“After returning from Rome to Florence, Benozzo went to Pisa, where he worked in the cemetery called the Camposanto, which is beside the Duomo, covering the surface of a wall that runs the whole length of the building with stories from the Old Testament, wherein he showed very great invention. And this may be said to be a truly tremendous work, seeing that it contains all the stories of the Creation of the world from one day to another. After this came Noah’s Ark and the inundation of the Flood represented with very beautiful composition and an abundance of figures. Then there follow the building of the proud Tower of Nimrod, the burning of Sodom and the other neighboring cities, and the stories of Abraham, wherein there are some very beautiful effects to be observed, for the reason that, although Benozzo was not remarkable for the drawing of figures, yet he showed his art effectually in the Sacrifice of Isaac, for there he painted an ass foreshortened in such a manner that it seems to turn to either side, which is held something very beautiful. After this comes the Birth of Moses, together with all those signs and prodigies that were seen, up to the time when he led his people out of Egypt and fed them for so many years in the desert. To these he added all the stories of the Hebrews up to the time of David and his son Solomon; and in this work Benozzo displayed a spirit truly more than bold, for, whereas so great an enterprise might very well have daunted a legion of painters, he alone wrought the whole and brought it to perfection. Wherefore, having thus acquired very great fame, he won the honor of having the following epigram placed in the middle of the work:

How beholdest thou birds, fish, and monsters prodigious, / Sylvan greenery or heavenly habitations? / Children, youths, mothers, and hoary-headed elders, / Their countenances live with the decorous charm? / Who fashioned these images of such varied form / Was not Nature, her genius engendering that brood. / This is the work of Benozzo: by his art their visages live: / O gods above, endow them with voices as in life!”

Throughout this whole work there are scattered innumerable portraits from the life; but, since we have not knowledge of them all, I will mention only those that I have recognized as important, and those that I know by means of some record. In the scene of the Queen of Sheba going to visit Solomon there is the portrait of Marsilio Ficino among certain prelates, with those of Argiropolo, a very learned Greek, and of Batista Platina, whom he had previously portrayed in Rome; while he himself is on horseback, in the form of an old man shaven and wearing a black cap, in the fold of which there is a white paper, perchance as a sign, or because he intended to write his own name thereon. In the same city of Pisa, for the Nuns of San Benedetto a Ripa d’Arno, he painted all the stories of the life of that Saint.

[…]

But to return to Benozzo: wasted away at last by length of years and by his labors, he went to his true rest, in the city of Pisa, at the age of seventy-eight, while dwelling in a little house that he had bought in Carraia di San Francesco during his long sojourn there. This house he left at his death to his daughter; and, mourned by the whole city, he was honorably buried in the Camposanto, with the following epitaph, which is still to be read there:

This tomb belongs to Benozzo from Florence who has painted nearby these histories. The people of Pisa donated this for him, 1478.” (vol. 3, pp. 122-125)