Easter Plays in the medieval German speaking world (Rebekka Gründel)

In the German Easter Plays, the name says it all: celebrating Easter and the salvation that it brings for Christianity is programme. Christ’s resurrection is depicted in great detail, using monologic and dialogic form to create an immersive and lively atmosphere.

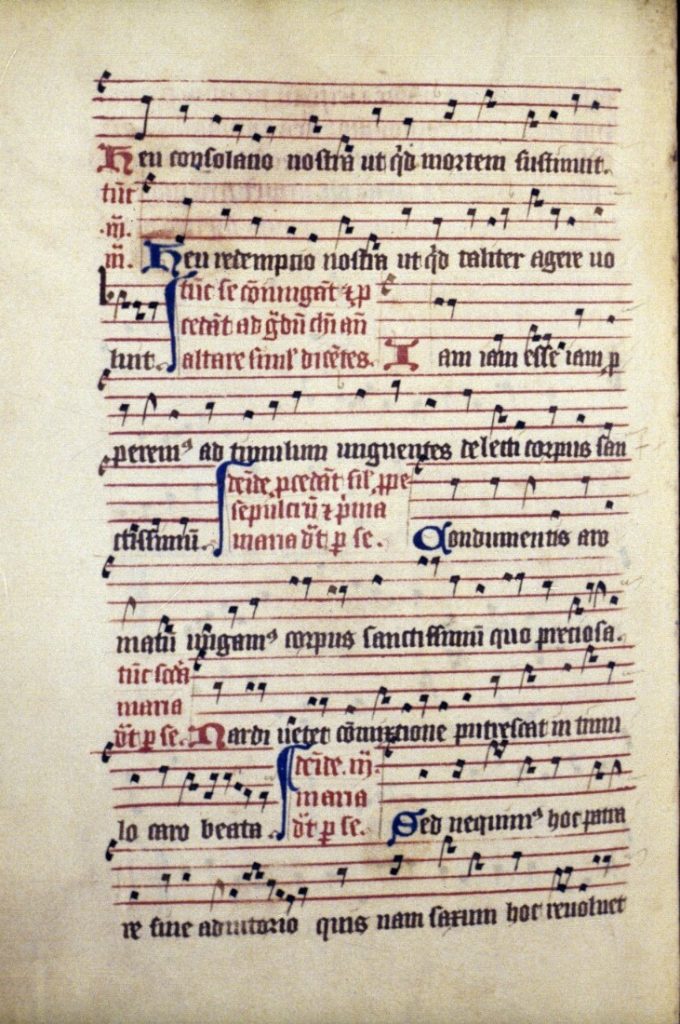

Oxford, Bodleian Library MS. Rawl. liturg. d. 4, fol. 130v.

Although claiming that the Easter Play is a direct development of the liturgical Easter celebration would be a form of literary Darwinism, it is clear that there is a strong connection between religious rite and theatrical play. Beginning as early as the 10th century and continued well into the early modern period (and beyond, even until today), the plays show the desire to not only understand the suffering of Christ in a spiritual sense, but to imitate it (Imitatio Christi), making it physically palpable and thus more accessible to the lay audience.

In most Easter Plays, the resurrection of Christ is depicted in a set framework: key elements are the guards at the sepulchre, Pontius Pilate, the Harrowing of Hell, the three Marys buying ointment and, of course, the resurrection of Christ. Although this seems repetitive at first, surviving examples of Easter Plays show that there was room to tweak and garnish the story, lightening the material with a humour, that today seems almost shockingly coarse. An episode that is especially embellished in the Innsbruck Easter Play and saturated with comedic undertones is the part of the play where the three Marys buy ointment for the body of Christ. Here the story takes a detour from the biblical topic to an incompetent Mercator and his witty servant in the so-called ‘Krämerspiel’(merchant’s play), a trope that gained such popularity that it can be found in several of the late medieval Easter Plays. In mixing biblical figures such as the three Marys, Jesus and Angel with contemporary characters from the urban setting (Mercator and Rubin) that are both identificatory figures and carry most of the comedic undertones, the Easter Play is a mix of spiritual and theatrical, serious and fun, and always one of the highlights of the religious year.

Reenactment: Mystery Cycle and ‚our‘ version (Haley Flower)

Enjoyment of the quips and quirks of the German Easter Plays are in no way limited to their contemporary medieval audiences. As part of the 2022 instalment of the annual Oxford Medieval Mystery Cycle, a team of medieval German enthusiasts adapted and performed the ‘Krämerspiel’ and Resurrection from the Innsbruck Easter Play. Oxford university and town people of the 21st century witnessed the same scenes of crude comedy and religious reverence as 13th century audiences; jokes about donkey farts are juxtaposed to Marys lamenting Jesus’ crucifixion; on-stage violent slapstick comedy precedes the Resurrection itself, announced by choirs of angels in Latin sung verse. Performed on consecrated ground at St Edmund’s Hall, sombre spirituality and mercantile antics are intertwined in this modern context, reflecting the medieval plays’ blurring of boundaries between depicting religious texts and comedic entertainment.

Difficulties faced by the group were how to ensure that Middle High German was understood by a modern audience in England. For the 2019 performance of the ‘Höllenspiel’ episode, or the Harrowing of Hell, placards were used with English translations of key textual elements, held up during the relevant actors’ speeches. Props were also used effectively to create comic effect, for example the character of the ‘helser’, or seducer, revealing a bra she had concealed in her coat pocket to clearly illustrate her role.

For the 2022 ‘Krämerspiel’ and Resurrection production, we wanted to try and situate English translations within the play itself; to this end, a narrator was introduced, with new narrative written in English by Haley Flower and interspersed throughout the original medieval German script. This addition fuses modern and medieval at two main levels of the performance: firstly, through the words themselves, which explain what has happened, or will happen to characters, while also expanding the medieval comic element through new satire; secondly, through the character of the narrator, who directly interacts with other characters, for example by pushing the Master of Ceremonies offstage. Modern and medieval comedy are made indistinguishable simultaneously to modern and medieval performance; while a communication barrier between medieval German and modern English is somewhat transcended, the universal languages of drama and entertainment fundamentally connect audiences centuries apart.

Insights into the Reenactment from the point of view of the character „Antonia“ (Kate Osment)

In Oxford’s Hilary term, I attended a reading group because my final exams are imminent and I wanted to improve my Middle High German. I expected that we’d read Easter Plays. What I didn’t expect, however, was that the experience would be so much fun, and that by the end of it I’d have promised to take part in an adaptation of a section of the Innsbruck Easter Play! When Rebekka Gründel and Melina Schmidt, who led the group, asked us if we’d like to act in a performance of the Easter Play – which takes place every year in Oxford – I somewhat spontaneously agreed.

Our adaptation, directed by Haley Flower, shows Christ’s resurrection but also a part of the so-called ‘Krämerspiel’. I’ve attached a photo of the cast, taken by Prof. Henrike Lähnemann after a read through of the play a couple weeks ago. The Krämerspiel’s humour is coarse and slapstick, relying on the well-known trope of an old man with a young wife who can’t satisfy her in bed. The more things change, the more they stay the same! Because of this, it’s the part of the Innsbruck Easter Play that modern audiences can best understand. The piety of the Middle Ages today seems very remote and isn’t easy for 21st century spectators to relate to, but a lot of the topics that made them laugh still make us laugh. I play Antonia, the merchant/quack doctor’s wife, a character who provides some of the Krämerspiel’s humour. She’s bawdy and rambunctious, with no reverence for either her husband or the three Marys and their holy mission; she first bursts onto the scene in a blast of rage at the Krämer (merchant) for selling ointment cheap. Their subsequent interaction is reminiscent of Punch and Judy. In the following scene, Antonia makes her final exit from the stage by eloping with her husband’s bone idle and libidinous servant Rubin, with a dirty joke as her parting shot.

Rebekka Gründel, Haley Flower und Kate Osment studieren u.a. Germanistik in Oxford und sind Mitglieder des Mystery Cycle unter Leitung von Prof. Dr. Henrike Lähnemann.

Weiterführende Informationen:

Harrowing of Hell from the 2019 Medieval Mystery Cycle https://www.seh.ox.ac.uk/mystery-cycle/harrowing-of-hell

Lecture Series ‚Easter Plays‘ by Prof. Henrike Lähnemann https://tinyurl.com/Osterspiele