A review on Jerold Frakes’ article “Viking, Vínland and the Discourse of Eurocentrism” published in The Journal of English and Germanic Philology, vol. 100 n°2 in 2001, pp. 157–199.

For centuries it has been taught in schools all around the globe that Christopher Columbus was the first European who had ever travelled to America, reaching it in 1492. Nowadays, we know that this was a misconception, as the discovery of a Viking settlement in L’Anse aux Meadows (Canada) in the 1960s proved that the Norse reached the North American coast five centuries before Columbus. The only medieval accounts of the Vikings’ presence on the other side of the Atlantic are the so-called Vínland sagas, which include the Eiríks saga Rauða and the Grœnlendinga saga written in the 13th century, almost exclusively transmitted in manuscripts from the 14th century or later.

Jerold Frakes shows in his enthralling article that Vínland is represented in these sagas by a certain type of colonialist discourse, now known as Eurocentrism. He analyses the patterns shared by the sagas and medieval Latin travel narratives. Both genres use Eurocentric motifs in the representation of the lands of the West. Frakes explains that the sagas are full of references to the Latin literary topoi because Icelandic writers received their education through the Latin Church and “were imbued by the great books of medieval pan-European Christian intellectual culture” (167). In order to prove his argument, he enumerates the Latin sources to which the Icelanders had access in the 13th century, as for instance Etymologiæ by Isidore of Seville.

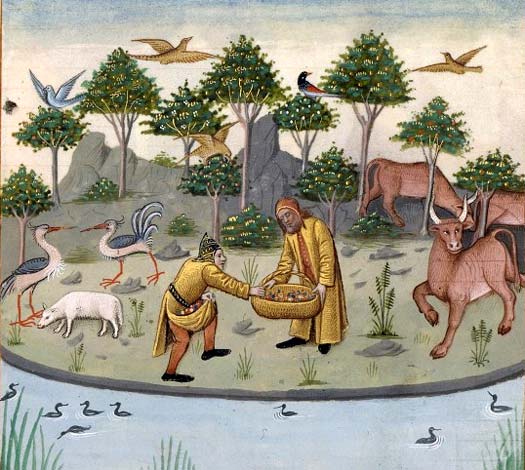

According to Frakes, the garden of Eden from the Bible and the Fortunate Isles from Greek mythology are the basis for describing Vínland as an earthly paradise with an idealized landscape. This land can appear as an Eden because the Skrælingar —the inhabitants of Vínland— are potentially Christians, but in the same time it is a mythic place due to its anomalous inhabitants, such as unipeds. However, the most striking features that transform the unknown land of the West into a biblical and mythological idyll are the self-sown wheat and grapes that inspired the name given to Vínland — the land of Wine. Since Antiquity, the motif of uncultivated grapes and grain growing in the western region has suggested a mythical place of abundance.

Frakes does not only focus on the discourse of idealisation, he also points out that the depiction of human communities from Vínland is similar to “the traditional paradigmatic mode of representing native inhabitants” (180). In the medieval Eurocentric discourse, culture, appearance and behavior of Europeans are assumed to be superior to that of non-Europeans. Likewise, the Native Americans of the sagas have no sense of trade, which makes them unable to judge the value of the Norse goods. They are said to be small, weak, remarkably ugly and they are represented as being dominated by violent animal instincts and thus incapable of rational thought.

Even though America was “officially discovered[1]” in the 15th century, the Eurocentric, stereotypical and fanciful perception of Native Americans did not disappear. Actually the opposite happened. As Frakes rightly points out, the “myths and legends, far from being refuted were actualized [and] the invention [was] reinforced by the discovery” (171).

[1] Frakes justly states that the word “discovery” is problematic. When Europeans are speaking about the “discovery of America” they place themselves in a very Eurocentric position and they deny that the continent was populated by autochthones for centuries before the arrival of Columbus.

1 Kommentar