Thor Heyerdahl was a scientist, an explorer, an author, an environmentalist and a global citizen. He went on an adventure when the world thought there were no more adventures left to have.

From left to right: Knut Haugland, Bengt Danielsson, Thor Heyerdahl, Erik Hesselberg, Torstein Raaby and Hermann Watzinger

(Heyerdahl, Thor. Kon-Tiki: ein Floss treibt über den Pazifik. Zürich: Schweizer Druck- und Verlagshaus, 1950)

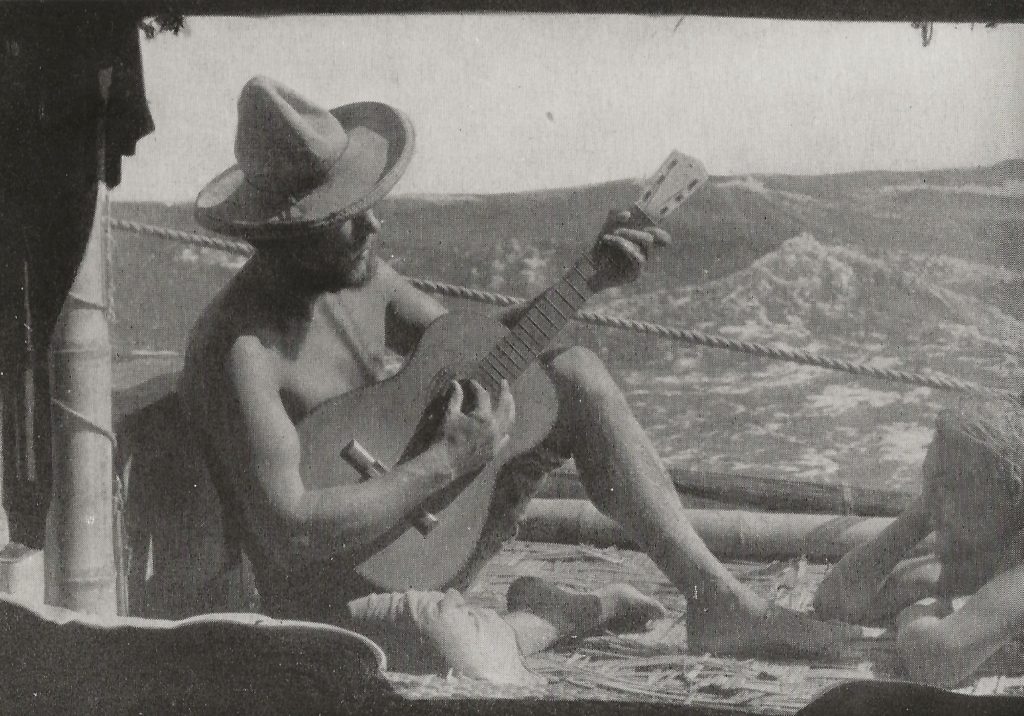

Thor Heyerdahl’s first expedition in 1947 was talked about all over the world. The journey across the Pacific Ocean on a balsawood raft named Kon-Tiki sparked interest in science and experimental archaeology and of all those looking for an adventure. The trip was supposed to prove Heyerdahl’s theory that the Polynesian Islands were settled by people from South America – a theory that was not taken seriously by his peers in the scientific field. To prove them wrong he used materials and techniques that were available to the indigenous people of South America to build the raft and set off for the journey in Callao in Peru with four fellow Norwegians and a Swede. The six-men crew took turns navigating and sailing and they arrived 101 days later on the Polynesian islands, thus proving the theory that it was possible to cross the ocean with a raft. Heyerdahl documented his journey in a travel diary and on film. A book called The Kon-Tiki Expedition: By Raft Across the South Seas was published by Heyerdahl in 1948 and a documentary named Kon-Tiki was released in 1950. Both were a huge success and the documentary even won an Oscar. The interest in the story was rekindled in 2012 by another movie called Kon-Tiki which was as well nominated for multiple awards as well. (IMDb Kon-Tiki 2012)

(Heyerdahl, Thor. Kon-Tiki: ein Floss treibt über den Pazifik. Zürich: Schweizer Druck- und Verlagshaus, 1950)

To this day Heyerdahl’s theorie is not accepted in scientific circles as there is overwhelming evidence that the settlers came from the west – the Southeast Asian Islands. But this is not the only problem with his theory. Other people have pointed out the racist implications of Heyerdahl’s theory. How come that Heyerdahl, the global citizen that advocated for peace and freedom all over the world, is seen as a racist? His theory, explained in his book The Kon-Tiki Expedition: By Raft Across the South Seas and scientific papers thereafter, states that a ‘race’ of white men travelled around the world to teach other races about agriculture and architecture. This ‘race’ had, according to Heyerdahl, light skin, blond or red hair and blue eyes. This ‘race’ travelled from Peru, where they educated the indigenous population, to the Polynesian Islands. The implications of this theory being, that only the ‘white race’ is capable of culture and knowledge.

Heyerdahl was not the only scientist who believed that similarities in culture and architecture all over the world indicate that there was one common source. The diffusionist theory speaks of the ‘white race’ as the originator of all cultural achievements and says that it is spreading its knowledge across the world by travelling to it and teaching it to the indigenous population. David Spurr remarks in his book The Rhetoric of Empire Colonial discourse in journalism, travel writing, and imperial administration that this theme was as well used in a broader colonial discourse by using different language for different achievements. The West ‚invents‘ different things, while others ’stumble over‘ inventions. (Spurr, 105) Heyerdahl’s theory was very controversial when he first published it because it contains concepts like ‚race wars‘ and ‚racial cleansing‘ and when the horrors of the second world war were still very fresh. Heyerdahl’s theory has been used together with the diffusionist theory by white supremacist to argue their supremacy in more recent years. (Holten, 178)

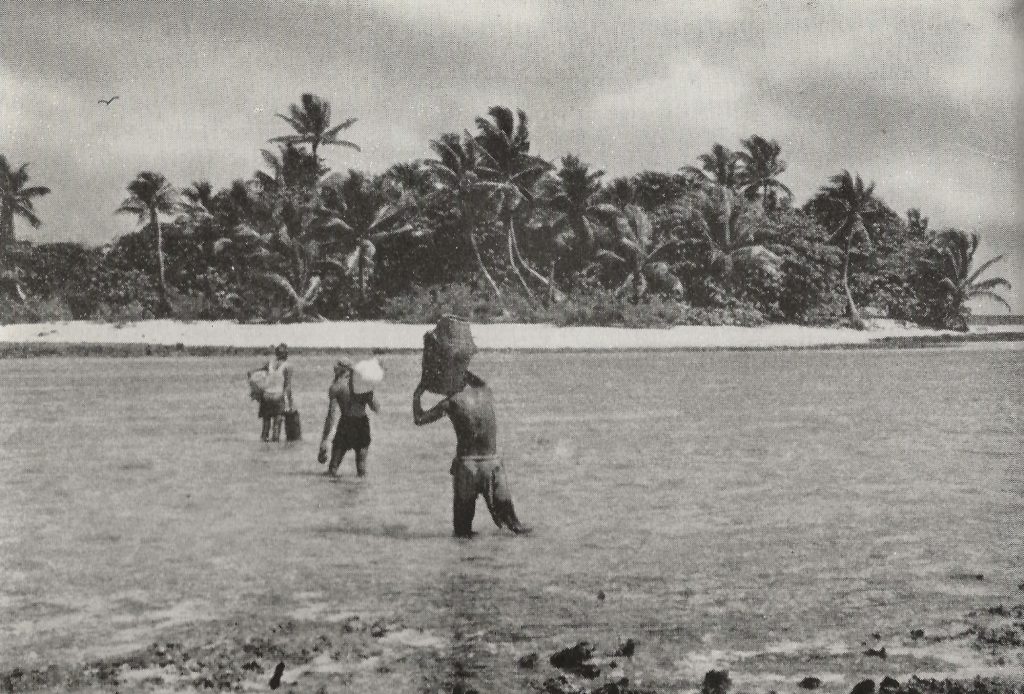

Victor Melander argues in his article A Better Savage than the Savages: Thor Heyerdahl’s Early Ethnographical Attempts and their Importance for the Development of the ‘Kon-Tiki Theory’ that Heyerdahl’s shattered expectations and illusions of the Polynesians Island led to him forming a theory that separated the Polynesians from their past. Melanders representation of Heyerdahl that is looking for the ideal man. Rousseau’s natural state of humanity serves as a paradigm for Heyerdahl’s theory. Society is a burden to humanity and a life without is the natural state. Heyerdahl went to the Polynesian Islands expecting that the people there would be free and living a paradise-like life. He also thought that people would not be plagued by the problems of civilisation and that the Polynisans would be friendly and hospitable people. (Melander, 382) Spurr calls this rhetorical method ‚Idealization‘ and claims that it is not only used by Heyerdahl but broadly in a colonial discourse. (Spurr 1993, 123-140)

(Heyerdahl, Thor. Kon-Tiki: ein Floss treibt über den Pazifik. Zürich: Schweizer Druck- und Verlagshaus, 1950)

(Heyerdahl, Thor. Kon-Tiki: ein Floss treibt über den Pazifik. Zürich: Schweizer Druck- und Verlagshaus, 1950)

(Heyerdahl, Thor. Kon-Tiki: ein Floss treibt über den Pazifik. Zürich: Schweizer Druck- und Verlagshaus, 1950)

In Heyerdahl’s book The Kon-Tiki Expedition: By Raft Across the South Seas, the idealization of the Polynesian Island is quite apparent. The book is filled with passages where Heyerdahl praises the islands as a paradise. There is plenty of food and the climate makes it possible to sleep under the sky without the need for houses or likewise. During their journey on the raft, there is plenty of food to be had, as the fish are literally jumping onto the raft. And at the end of their journey they are greeted by friendly Polynesians who hold a festivity in their honour that lasts for days. But not only the land and climate is idealized – Heyerdahl describes his life on one of the islands in the first chapter:

„The civilized world seemed incomprehensibly remote and unreal. We had lived on the island for nearly a year, the only white people there; we had of our own will forsaken the good things of civilization along with its evils. We lived in a hut we had built for ourselves, on piles under the palms down by the shore, and ate what the tropical woods and the Pacific had to offer us.“

(Heyerdahl 1978, 11)

In the other versions of the book, this paragraph is followed by Heyerdahl’s thoughts, that he and his wife were living like the first primitive people in a spiritual and physical way like the people who were living on the island before the colonizer arrived. (Heyerdahl 1950, 10) The Polynesian Islands were colonized by the French at the time Heyerdahl undertook his journey.

Heyerdahl’s search for natural state of humans is apparent in his musings on his own life on the island as well as when he talks about other people and places. One of the Polynesians chieftains he meets is described as a “untainted child of nature”. (Heyerdahl 1950, 275) He is portrayed as a stereotypical Polynesian but loses this position to a man who can speak French, read and write and calculate. Necessary skills in a new world where the Islands trade with each other and are ruled by the French so that the village is not being cheated when making business.

Heyerdahl’s disdain for civilisation and the people living in it leads to him believing himself to be closer to the natural state of humanity or as Melander calls it to be A Better Savage than the Savages. The journey as well as the theory behind it is problematic, to say the least. It is a white man’s journey to prove the supremacy of the ‚white race‘ and to deny the Polynesians their own history and accomplishments.

References

- Heyerdahl, Thor. Kon-Tiki: ein Floss treibt über den Pazifik. Zürich: Schweizer Druck- und Verlagshaus, 1950

- Heyerdahl, Thor. Kon-Tiki: Across the Pacific by Raft. Pocket Books, 1978

- Holton, Graham EL. „Heyerdahl’s Kon Tiki theory and the denial of the indigenous past.“ Anthropological Forum. Vol. 14. No. 2. Taylor & Francis Ltd, 2004.

- Melander, Victor. „A Better Savage than the Savages: Thor Heyerdahl’s Early Ethnographical Attempts and their Importance for the Development of the ‘Kon-Tiki Theory’.“ The Journal of Pacific History 54.3 (2019): 379-396.

- Spurr, David. The rhetoric of empire: Colonial discourse in journalism, travel writing, and imperial administration. Duke University Press, 1993.

- “About Thor Heyerdahl.” The Kon-Tiki Museum, www.kon-tiki.no/thor-heyerdahl/.

- „Kon Tiki.“ IMDb, www.imdb.com/title/tt1613750/.