Over the past couple years since How to Train Your Dragon first came out in 2010, there have been a handful of articles about its connection to postcolonialism. The mentions, however, have gone from academically acclaimed to dubiously religious, which is why I have decided to go over the topic once more, with feeling.

To Be a Viking, or Not to Be

Hiccup, our main character, lives in the village of Berk. Despite being “twelve days north of hopeless and a few degrees south of freezing to death” (Sanders and DeBlois), it does seem quite nice. As Hiccup himself describes it “the only problems are the pests” (Sanders and DeBlois). The first reference to dragons in this story is told with seeming irony: Hiccup compares the dragons to mice or mosquitoes, even though the dragons keep ravaging their livestock. Throughout the movie it becomes clear how hard the people of Berk try to contain the humanization of dragons. An example would be when one of the youths of Berk, Snotlout, calls dragons “stuff”: “Why read words when you can just kill the stuff the words tell you stuff about?” (Sanders and DeBlois). The differentiation between white people (and yes, every human in How to Train Your Dragon is white, which makes a black dragon sort of pop out) and non-white people in the real world too often leads to understanding the latter as threateningly primitive and barbaric, which sets an ideological basis for colonization and exploitation (Antor 35). Ergo: Dragons are supposed to be primitive, savage and exotic to justify their murder: HICCUP (V.O.) (CONT’D) A Zippelback? Exotic, exciting. Two heads, twice the status” (Sanders and DeBlois).

Hiccup and his village are Vikings — or so they repeatedly claim to be: “We’re Vikings. We have stubbornness issues” (Sanders and DeBlois). Horned helmets, stylized figureheads and roof gables coded in a Viking aesthetic (comparable with the houses in Whiterun in Bethesda’s game Skyrim or in Ubisoft’s recently released Assassin’s Creed Valhalla) are meant to lull the audience into a dulling sense of historicity that keeps questions at bay. The change of perspective allows the audience to see the Other differently, but also to relativize the actions of the Own (Gess, 147). Hiccup even explicitly says that “Everything we know about you guys [dragons] is wrong” (Sanders and DeBlois), and yet! White men murdering a race they know nothing about and do not understand as a people? Vikings…killing…dragons? Yes, yes, and on the story goes “Because killing a dragon is everything around here” (Sanders and DeBlois). Duh.

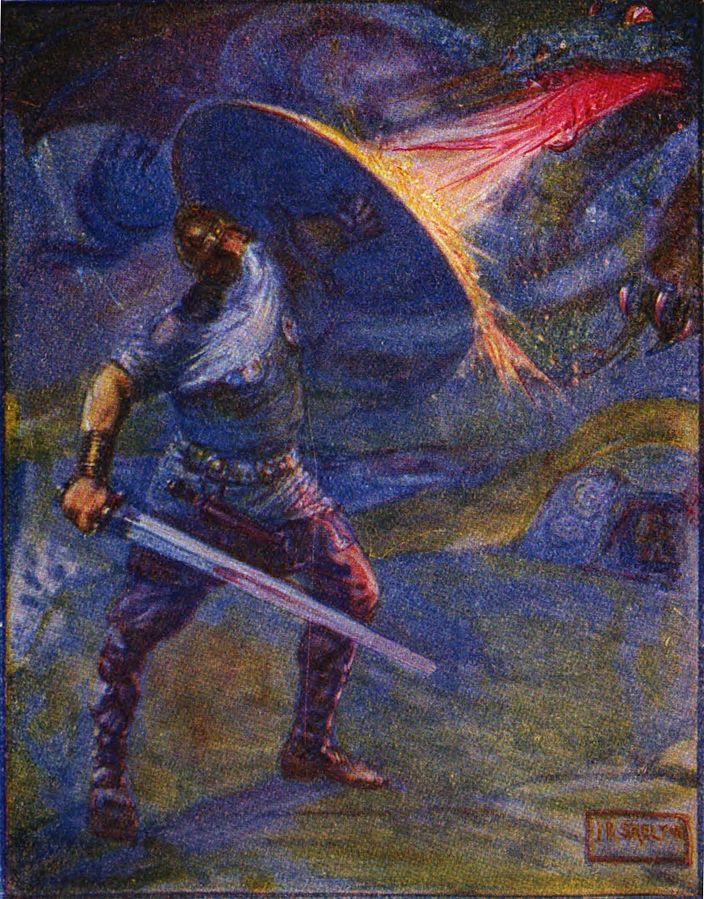

„Now he belched forth flaming fire.“ by J. R. Skelton in Henrietta Elizabeth Marshall’s (1908) Stories of Beowulf, T.C. & E.C. Jack

Œdipal Oddities

There is a difficult father-son relationship in How to Train your Dragon, between the traditionalist, militaristic and authoritarian father and the more progressive son, a strong, œdipal trope that might reminisce of Walter Hasenclevers expressionist drama The Son (Hasenclever and Schulz). This same relationship is to be found in another postcolonially interesting movie, Klaus (Pablos).

To quickly pull you into a sidebar about Klaus (Pablos) — and yes, I will keep it short, I promise: the narrator and protagonist, Jesper, is a very privileged young white man. This is not a secret to his father, the Postal Master, who sends Jesper to Smeerensburg to establish a working postal office. It is important to note that all postal workers are white and that the Royal Postal Academy looks like a military academy. There is a drill instructor, called Sergeant, who counts how many crunches the “cadets”, i. e. the young postal workers, are doing. The music underlines the scene at the Royal Postal Academy with military drums that bring to mind Donny Osmond’s rendition of Mulan’s 1998 “I’ll Make A Man Out Of You”. We learn that Jesper only got into the Royal Postal Academy due to his father’s influence, and that like Hiccup, he is a great disappointment to his father. This is why Jesper is sent to Smeerensburg in the first place, a fictional, very cold island clearly set in the far, far North. The job Jesper’s father sends him to do is a punishment for his lavish lifestyle. This was not a short sidebar, I am a liar, but now that you are here you are glad, are you not? I, for my part, regret nothing.

Hiccup’s father, the chief of the tribe, is called Stoick, and he is a strong supporter of keeping the status quo of killing as many dragons as possible. He is, in fact, so much into killing dragons that his interest for his only son depends on Hiccup murdering dragons. This is shown right before he disinherits Hiccup for being unable to kill a dragon during a gladiator-esque event in which the best student of Dragon Training School (whose teacher is Gobber, the Blacksmith who lost two limbs to dragons — is that really the best teacher you could afford, Berk?) gets to…drum rolls…kill a dragon. Stoick announces proudly that “Today, my boy becomes a Viking. TODAY, HE BECOMES ONE OF US!” (Sanders and DeBlois). And Hiccup really wants to be the sort of person who can kill a dragon “I just want to be one of you guys,” Hiccup tells Gobber at one point (Sanders and DeBlois).

Hiccup differs from Jesper, who does not particularly heed his father’s advice nor need his approval. Now, you might ask, “but isn’t Stoick right, should dragons not be ‘killed on sight’ (Sanders and DeBlois), after all, they are ‘extremely dangerous’ (Sanders and DeBlois) beasts killing the villagers and their livestock?”. And although Hiccup cannot kill a dragon, he is so obsessed with the idea of earning his father’s respect (and a girlfriend) that he invents a sort of gun that shoots bolas and with it brings down the most feared dragon of them all: a Night Fury.

“I’m going to kill you, Dragon. I’m gonna cut out your heart and take it to my father. I’m a Viking. I am a VIKING!” he exclaims…yet Hiccup does nothing of the sort (Sanders and DeBlois). But a Viking is only a Viking if dragons are killed by said Viking. Even their sails bear pictures of dragons being murdered. So let us call that what it is: othering. The people of Berk define themselves by othering dragons, i. e. they identify through demarcation from The Other (Babka 23). Hiccup is confused about the Night Fury’s decision not to kill him, since all he knows about dragons, is that “a dragon will always, (with a stern look to HICCUP) always go for the kill.” (Sanders and DeBlois).

A Dragon, a Viking and a Black Man Walk Into a Bar

And thus Hiccup slowly unlearns the Viking propaganda, and initially slims down his chances of getting a girlfriend. His first approach is to try and tame the Night Fury like an animal: he brings it raw fish. And this approach is not entirely misplaced, seeing as dragons have pet-like attributes, like a love of catnip or hunting light (and probably laser-points) on the floor. Some dragons even purr. Like a bird with its chicks, the Night Fury tries to share half the fish with Hiccup by puking it out, and Hiccup ends up eating the very disgusting offering.

The two spend a lot of time together in the woods. When the Night Fury starts mimicking Hiccup by drawing in the sand with a branch it becomes clear that this is more than a mere animal Hiccup is dealing with. The Night Fury gets angry when Hiccup steps on his piece of art, but does not growl when he steps on the floor next to the lines in the sand. Once Hiccup has understood this, the Night Fury lets him touch it. From that moment on, the Night Fury gets a name — Toothless — and becomes an individual.

Let us at this point not forget how closely the right to an identity and personhood hangs together with a name. The biographical French movie Chocolat (Zem) deals a lot with this exact subject. It tells the story of the formerly enslaved black man who becomes France’s famous clown Chocolat. Throughout the movie, Chocolat (Omar Sy) gets three different names: “Kananga”, the racist name given to him by the circus to play a black cannibal, “Chocolat”, the name given to him by his co-star Foottit for the slapstick kind of act in which Chocolat is the butt of the joke, and at last “Rafael Padilla”, a name he chooses himself as he is hired as an actor, a job he does out of love for the art and not out of necessity.

But back to the Vikings. Not everyone is able to see Toothless’ identity and personhood, and even Hiccup forgets it from time to time. When Astrid discovers what Hiccup has been up to, he takes her for a ride through the air on the back of Toothless. Hiccup still uses pet-commands with Toothless “Toothless? Down. Gently.” (Sanders and DeBlois), which of course, the now liberated Toothless is not having any of. The script of the movie describes the revenge Toothless takes on Astrid “Toothless leers mischievously. He spreads his wings slowly. With a WHOP, they fill with the updraft. Toothless releases the tree, tucks in his legs, and HOVERS in place.” (Sanders and DeBlois). Hiccup responds with more dehumanizing language “Bad dragon” (Sanders and DeBlois) and “You useless reptile” (Sanders and DeBlois). But he does not control Toothless who “ROLLS and PLUMMETS toward the coastline far below. Astrid SCREAMS. Toothless rockets over the ocean waves, deliberately dipping them in the froth” (Sanders and DeBlois). Toothless is never a less-than-human thing, or an animal: Toothless’ personality is graspable throughout the whole of the movie. The Vikings just cannot see it.

It becomes clear after Hiccup, Astrid and Toothless see the dragons’ queen, that the dragons are indigenous to the land. Nicola Gess writes in an article on primitivism and exoticism that “primitive thinking“ historically used to be attributed to three groups of people considered Others: indigenous people, children and mentally ill people (146). It was a common, albeit incredibly racist understanding in the early 20th century that indigenous people did not have the capacity to have their own culture or history because of their assumed “simplicity” (Gess, 146). Hundreds of dragons in the movie fly to an island which hides an even bigger dragon. There they drop the stolen livestock down the giant dragon’s gaping maw. Astrid sees the sacrifices or feedings of the giant dragon not as an elaborate cultural ritual but compares the scene to bees and their queen. When they come back from this sighting, Toothless is nothing but a pet to Astrid “Hiccup, we just discovered the dragons’ nest…the thing we’ve been after since Vikings first sailed here. And you want to keep it a secret? To protect your pet dragon? Are you serious?” (Sanders and DeBlois). All of this makes the Vikings the colonial force who took the indigenous land. Only when Hiccup stands up for Toothless and insists they do not tell his father immediately about the dragons’ lair, does Astrid give in.

When Hiccup’s plan fails, Toothless is captured. In a heated argument with his father, Hiccup inadvertently surrenders his knowledge about the dragons’ nest. Immediately, the enchained and enslaved Toothless is to lead the Vikings to the nest. The Vikings attack the nest, which to say the least, does not bear good for the Vikings.

Hiccup, Astrid and all the young villagers from the Dragon Training School quickly tame more dragons and go to the Vikings’ rescue. This is when Gobber, the blacksmith, points out to Stoick that Hiccup is, “Every bit the boar-headed, stubborn Viking“ that he ever was (Sanders and DeBlois). The script denotes that “Stoick is speechless”, but in the movie Stoick seems to be nodding to Gobber approvingly (Sanders and DeBlois). In the end, Stoick rescues Toothless from drowning and apologizes for all of his actions to Hiccup, not to Toothless whom he enchained. Toothless and Hiccup defeat the giant dragon and Toothless becomes the new Mother of Dragons! … I mean the head of the dragons’ hoard. Happy ending for everyone…or is it? After everything, the movie ends with dragons being called nothing more than pets. Not until the third movie are all the dragons freed and accepted as fully sentient beings equal to humans (DeBlois).

References

Antor, Heinz. «Weiterentwicklung der anglo-phonen postkolonialen Theorie». Handbuch Postkolonialismus und Literatur, J. B. Metzler, 2017, pp. 26–37.

Babka, Anna. «Gayatri C. Spivak». Handbuch Postkolonialismus und Literatur, J.B. Metzler, 2017, pp. 21–26.

Gess, Nicola. «Exotismus/Primitivismus». Handbuch Postkolonialismus und Literatur, J. B. Metzler, 2017, pp. 145–49.

Göttsche, Dirk, u. a., Herausgeber. Handbuch Postkolonialismus und Literatur. J.B. Metzler, 2017.

Hasenclever, Walter, und Georg-Michael Schulz. Der Sohn: ein Drama in fünf Akten. Reclam, 2003.

Pablos, Sergio. Klaus. Netflix, 2019, https://www.netflix.com/watch/80183187. Accessed 20.01.2021.

Sanders, Chris, and DeBlois, Dean. How To Train Your Dragon. Universal Studios, 2010, https://www.imsdb.com/scripts/How-to-Train-Your-Dragon.html. Accessed 20.01.2021.

DeBlois, Dean. How to Train Your Dragon: The Hidden World. Universal Studios, 2019.

Zem, Roschdy. Chocolat. Gaumont, 2016.

1 Kommentar