Journalism on the Caribbean Islands During Danish Colonial Rule

Journalism has always been an important tool in communication, but also, just as importantly, a means to fight for civil rights. For life in the Danish colonies, newspapers had essential functions, for everyday communication, identity building and advocacy for civil rights.

During the late 18th, 19th and early 20th century, several newspapers were printed on the Caribbean islands, some of which ran for a number of years, whereas others were only published for a handful of issues. In recent years, numerous newspapers have been digitized by the Kongelige Bibliotek, which is based in Copenhagen. Among these are The Royal Danish American Gazette, The Saint Croix Bulletin and the Saint Thomas Herald.[1] This digitization enables more people, who otherwise would not have access, to read the newspapers. Naturally, this allows different studies on the source material to be made. For the context of this blog. I’ll discuss how the material can be analysed from a postcolonial standpoint.

The main islands under Danish rule were St. Croix, St. Thomas and St. John (additionally, smaller islands surrounding the main ones belonged to the Danish Crown). Danish rule lasted from 1671, when the trading company Danish West India Guinea Company annexed the then uninhabited island of St. Thomas, until 1917, when the US bought the islands.

During the 200 years of legal slave trade, the islands were a huge financial aid to Denmark. Therefore, Charlotte Amalie, the capital city of St. Thomas, used to be the richest city under the Danish crown. It is estimated that 100,000 slaves were transported over the Atlantic in ships flying the Danish flag (Baggesgaard 467). Thousands died on the journey, and those who survived were forced into strenuous labour on the Caribbean sugar plantations. Therefore, the port of St. Thomas also acted as a transfer site to transport the slaves to other colonies in the region (Gøbel 53-54). Slavery was officially abolished by a decree from the Governor of St. Thomas, Peter von Scholten, in 1848.

Even though the islands were under Danish rule, there were never many Danish residents. Most Danes on the islands acted as government officials. The islands were culturally and linguistically diverse, which also meant that Danish was never the most spoken language on the Islands. While Danish had the standing of an official and administrative language, English was favoured among the inhabitants. The language of the press was also mostly English (Blaagaard 23).

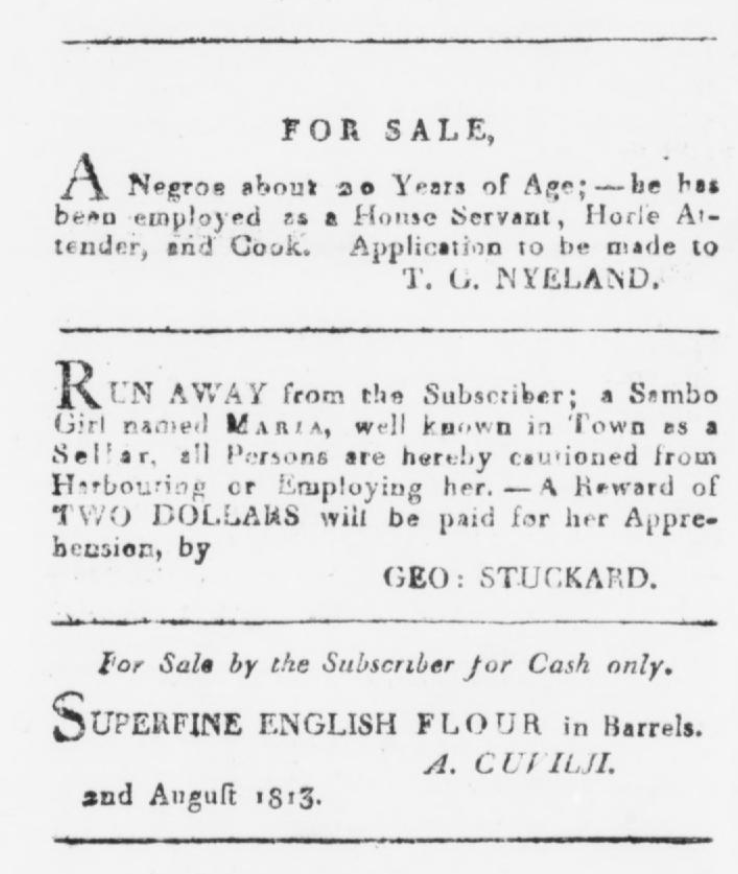

Most newspapers were similar in their layout and the themes they discussed, which consisted mostly of everyday topics, even though for the modern reader, it certainly is jarring to read about enslaved people being offered for sale next to listings of bread prices.[2]

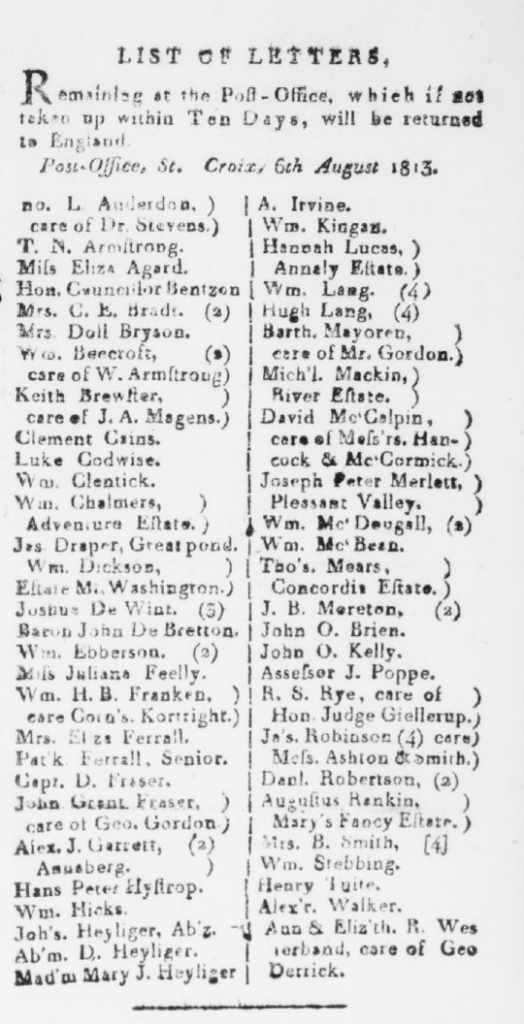

Another prevalent topic in the Danish colonies were postal procedures. In The Old St. Croix Gazette, a list of letters that had not yet been collected, was printed. Interesting here is that the newspaper cautions that the letters, if not collected within ten days, will be sent back to England. The Old St. Croix Gazette seemed to be directed towards British people, or at least people who had more or less frequent contact with the United Kingdom. It stands to reason that different papers for different nationalities existed. Although nationality probably is the wrong word, as the colonies were culturally and linguistically diverse and connections to the respective mother country (of each newspaper’s readership) were scarce and in some cases nonexistent.

Since the newspapers circulated in small numbers and had very few people working on them, the printers and writers were represented strongly in their papers. The Old St. Croix Gazette’s printer, Peter Lake Clark, is named at the end of every edition and he is also mentioned throughout the issues. In issue no. 65, published Friday the 13th of August 1813, a notice reading: Wanted to purchase or hire. A COOK. Apply to the printer. was published. Clark, in this instance, is solely referred to by his standing as the printer, which implies that he was known for his work on the newspaper.[3] Most people printing, writing and editing papers had other means of making a living. Finances were always a problem and many had to leave their work on the papers fairly quickly due to being unable able to keep the newspaper up and running, meaning the papers were run by citizen journalists.

David Hamilton Jackson, born to formerly enslaved parents in 1884 in St. Croix under Danish rule and died in 1946 after the purchase of the colony by the US, was famously the founder and editor of The Herald from 1915–1925, but he also wrote for it and adamantly advocated for labour rights in the Caribbean and in Denmark. While most of his requests for reforms, such as workers’ rights to own land, were denied, his appeal to withdraw “the law demanding royal permission to publish” was successful (Blaagaard 47). Thus, David Hamilton Jackson was the founder of the first independent newspaper in the Caribbean colony (47). He also travelled to Copenhagen several times to give public talks fighting for workers’ rights and living conditions. This fight was also transmitted in The Herald. Having said this, it is important to mention that The Herald did have many adversaries, especially with the islands’ white plantation owners, who feared a bloody uprising of the plantation workers.

Therefore, the newspapers on the islands served important functions during colonial rule. On the one hand, they functioned as communicative devices meant to facilitate a seamless everyday life, and on the other hand, they were instruments for political activism.

Citizen journalism is inherently linked to its location, as the journalistic system in colonial states developed differently and later as in European nations. Post-colonial studies, therefore, focus not only on relations between different actors and nations, but also on the location as such; on the landscape in which certain occurrences happen and how these surroundings affect them. Hence, their context is not only culturally, but also locally determined.

To round off this blog entry, I’d like to present the following hypothesis, Namely that identity in the colonies was not shaped by nationalities but by an interconnected understanding of the world. In the colonies, newspapers were especially important in establishing a common, unifying identity. Especially in heterogeneous places such as the Danish West Indies, where several cultures and languages existed alongside each other. The newspapers assembled a broad spectrum of events and thus gathered facts and reports into one source of information. The papers were also relevant to the whole readership, as they focused on life in the colonies, as the papers carried many advertisements and statements from the subscribers themselves. Each newspaper, therefore, established a communication system for its readers.

The newspapers on the islands also collected different papers from mostly European countries. These papers were then read and summarised in the local newspapers. There must have been a system in place which enabled each printer to read papers in several different languages, so they could transmit information from all over the world. This further corroborates not only the linguistic diversity on the islands, but also its global character: „[…] the Danish colonies to a large extent lacked a common language [which] challenges the argument that print capitalism is crucial to sustaining a colonial sense of belonging to the nationality of the colonial ruler.“ (Blaagaard 24). The newspapers on the islands may be seen as an example of how the press was utilized to work against a national identity and instead stressed the international character of the islands and their social and economic lives (Baggesgaard 473). The newspapers present an already interconnected world which shaped the resident’s identity on the colonial islands.

The newspapers of the Danish West Indies present a deeply personal and multifaceted view into life on the islands. They give insight into life in the 19th and early 20th century, which can be made very productive for postcolonial studies.

References

Baggesgaard, Mats Anders. Precarious Worlds. Journal of World Literature 1.4 (2016): 466–483.

Blaagaard, Bolette. Citizen Journalism as Conceptual Practice. Rowman & Littlefield International, 2018.

Gøbel, Erik. The Danish Slave Trade and its Abolition. Brill, 2016.

[1] cf. Det Kgl. Biblioteks mediesamlinger [07.11.2020]

[2] cf. Det Kgl. Biblioteks mediesamlinger [11.11.2020]

[3] cf. Det Kgl. Biblioteks mediesamlinger [11.11.2020]

Titel image: The Old St. Croix Gazette (1813), cf. Det Kgl. Biblioteks mediesamlinger [27.01.2021]