In Norse mythology, the whole world is situated on a giant tree: Yggdrasil, the world tree. At its roots live three mythical beings called Norns who water the tree and determine every person’s destiny and ultimately the destiny of the entire cosmos.[1]

The symbol of roots has played a vital role in the reception of Norse Mythology. Often, people interested in Old Norse culture have made claims about reconnecting to their roots, which, politically, can be very controversial given the history of how Old Norse texts have been used in nationalistic narratives and ultimately in the propaganda of the Third Reich.[2] But the idea of roots in combination with Norse Mythology still plays an important role in at least one current movement: a group of religions called Heathenry. My goal for this blog entry is to introduce the general public and scholars who are not very familiar with these religions to their main aspects, explain different political stand points within them and especially to criticise certain ideas in these religions concerning the concept of “roots.”

Heathenry is a new religious movement that includes a variety of different beliefs, practices, as well as political and social identities. The term Heathenry is mainly used in the English-speaking world and refers to groups whose main defining points are the veneration of Germanic deities and a focus on medieval texts such as the Old Norse Eddas and Sagas. Combining Germanic religion in general with Old Icelandic literature can be contested in scholarly perspective, but it is an important aspect of Heathenry in a religious sense. This has mostly practical reasons: A common narrative within Heathenry is the idea of “reconstructing” Germanic religions.[3] From a scholarly perspective, an actual reconstruction of these religions is of course impossible, not only because it is impossible in our society, but also because there are barely any reliable sources on Germanic religions. Since it is impossible to (re)construct something mainly out of archaeological findings and place name studies, which is all we have for some areas, most Heathens will make reference to Old Icelandic literature, even if they’re attempting to reconstruct the religion from another Germanic region. This is of course rooted in a religious perspective and not a scholarly one.

Heathenry can be seen as a subgroup under the umbrella term Neopaganism, which describes different religions that take inspiration from pre-Christian cultures and venerate nature in some way. However, this clear subdivision is especially used by practitioners in the English-speaking world and there aren’t many actual boundaries between Heathen and other Neopagan groups.[4] I haven’t observed such a clear distinction in other languages either. In German, my mother tongue, practitioners tend to either use the terms neuheidnisch/neopagan interchangeably, simply refer to their specific religious group’s name or prefer the term neuheidnisch/Neuheide, because it is more commonly used and therefore more easily understood by outsiders. In both German and English usage, the term «Neopagan» refers to a very broad range of religions inspired by different cultures, time periods and regions ranging from Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia to the British Isles and Scandinavia. Since this blog is written in English, I will focus on the English usage of the term Heathen and the groups and ideas connected to it. The way I use the terms here may give those who are new to this topic an overview of the general discourses within Neopaganism and Heathenry as they are used in the English-speaking world, but especially in North America.

In popular discourse, Heathenry has often been linked to politically far right circles. This is a simplification, since many practitioners do not have such views. But there is a very vocal far right minority within the movement and some controversial narratives circulate even in politically moderate wings of the movement. One of these controversial narratives is the focus on roots which is sometimes combined with ideas on race. The scholar Thad N. Horrell analyses this narrative in relation to postcolonialism. For my extended review of his article concerning the topic, please click here.

It is very common in Heathenry, just like in other Neopagan movements, to focus on ancestry or family in one way or another. This includes both ancestors that one actually knew, as well as imagined ancestors, such as the pre-Christian European population and their culture. These movements can therefore also be analysed as examples of “invented tradition”, a concept developed by Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger (click here for my review of their work). Following this train of thought, Heathenry is inventing a tradition by creating links to a long gone past and by implying continuity with this past. Said continuity is perceived through the focus on historical research and on “correct” practice based on scholarly findings. I would argue that one of the appeals of Heathenry and Neopaganism as a whole lies precisely in this invention of tradition.

To clarify, I do not think that this is per se a bad thing. These, albeit imagined, connections to the past must be seen on a spectrum. This can already be observed in the discussions within Heathenry on who is allowed to practice the religion. Heathens have two main stances on this subject, namely the universalist stance and the völkisch stance. Practitioners taking the universalist stance argue that everyone, regardless of their ethnic background, can be called by Germanic gods and therefore practice the religion. Practitioners taking the völkisch stance, on the other hand, believe that only those with Germanic or Nordic ancestry are able to practice the religion, since to them it is a strictly “ancestral” faith.

To further illustrate this spectrum, I would like to differentiate between what I call “roots” and what I call a “construction of ethnic ancestry”. I define roots as something which is entirely based on learning and acculturation. Roots can be connected to one’s upbringing, as they are in the traditional sense of the word, but they can also be based on things one has encountered outside of one’s family. To me, roots are the cultural items, the stories, art, music and practices an individual turns to, to feel safe and to explain their role in a complex world. For instance, one could find their roots in a church attended by one’s family, but one could also find one’s roots in historical reenactment or medieval markets. Roots are always connected to some form of community and therefore to a history, be the continuity with that history real or imagined. “Roots” by this definition are something necessary, since everybody needs a place and a community that reassures them in life. Furthermore, roots are not exclusive and one can be rooted in several different practices and communities. Heathenry and Neopaganism as a whole can offer “roots” in this sense to practitioners, which in itself does not have to be an issue. But the discussion about roots becomes extremely biased when people try to link them to a construction of “ethnic ancestry.” By that I mean linking an invented tradition and cultural heritage from Scandinavian and Germanic countries to “genetic heritage.” I think this is something that can happen rather easily within Heathenry, because it focuses on ancient civilisations and tries to link them to the modern world. Norse mythology was also very popular in nationalistic narratives of the 19th and 20th century and ultimately used heavily in Nazi propaganda, which sadly still attracts people with such an ideological background to Old Norse culture.

There are clear problems concerning roots in relation with concepts on race in Heathenry and Neopaganism, but the way they show themselves is not often clear. There is only a small minority of people in these movements who openly espouse racist worldviews. But, because Neopaganism emerged during the time of national romanticism,[5] it carries many implicit ideas that are harmful and easily bent into nationalistic and racist narratives. In spite of being an invented tradition, which I do not perceive as a bad thing, some practitioners in movements like Heathenry pretend their religion is closely tied to their actual ancestors, who in reality, if they’re from European descend, have most likely either been Christian or Jewish for at least a thousand years. The claim that Heathens “honour their ancestors” by practicing their religion, seems faulty to me in so far that many of them seem to be referring to their blood relatives.[6] To me, the logically consistent way to honour these ancestors would not be becoming a Heathen, but, following this line of thought, being a traditional Christian or Jew. What is the implication of “honouring your ancestors” by becoming a Heathen? To me, this looks like the very suspect idea that certain groups of people, certain “races,” are genetically predisposed to certain types of religions. This idea can be clearly disproven[7] and has overt racist elements. It is expressed very openly by far-right Heathen groups like the AFA, which was classified as possibly the biggest hate group in the United States by the Southern Poverty Law Center.[8]

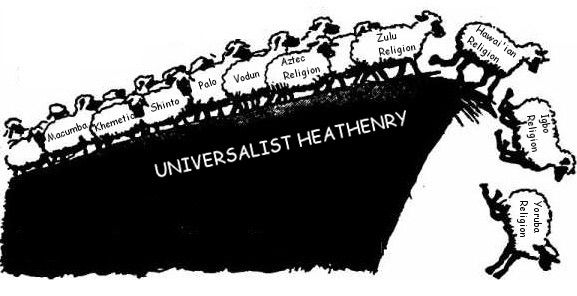

In its worst iterations, the “construction of ethnic ancestry” has clear links to Nazi ideology, as can be exemplified not only by the AFA, but also by the group The Odinic Rite, which was founded in the USA, but currently also has a larger following in Spain.[9] The Odinic Rite was founded by the Danish immigrant Else Christensen.[10] She was inspired by the books by Alexander Rud Mills, an Australian who aspired to create a religion by combining Old Norse sources with Nazi ideology.[11] Christensen herself embraced an ideology called “tribal socialism” and advocated for small, tribal groups of white Odinists living self-sufficiently off the land.[12] Here again, one sees the focus on a “tribe,” the idea of racial differences and “ancestral” or more clearly “racial religion.” This is the view of the völkisch stance in modern Heathenry, which perceives the religion as “ancestral” to people of Germanic origins. Here, there is also the clear implication that Heathenry is an “Indigenous religion” that must be protected by not allowing foreign influences to change it. The cartoon below illustrates this, by criticising the universalist stance in Heathenry. The different sheep walking over the cliff are named after Indigenous religions that are ultimately destroyed by following the universalist stance.

A more ambivalent view within Neopaganism as whole is a tendency to perceive oneself as the underdog and victim.[13] This view has some truth to it: Neopaganism is a group of minority religions that often attracts people from minority groups such as the queer community.[14] But this view of the underdog is also defined by some degree of opposition against Christianity. By using the words (Neo)Pagan and Heathen, which stem from Christian discourses labelling “the other”, practitioners implicitly criticise Christianity and position themselves as an alternative to it. For many Neopagans, this remains implicit however, and does not lead them to actually oppose Christianity. Some Neopagans even embrace Christianity by openly following both Christian and Neopagan traditions.[15] Here, using the term Neopagan or Heathen seems to be connected to practical reasons: It has been used for some time and can be easily looked up online, which might make explaining it to outsiders easier. In spite of all this, the idea of Christianity as an opposing force can be used in very negative ways. This can be seen in Thad N. Horrells article “Heathenry as Postcolonial Movement”, which discusses how politically far right individuals see themselves as the “victims” of Christianity who “colonised” their ancestors. Here the “victims” are generally white people who are in a position of power compared to actually colonised people like Native Americans. Comparing the medieval history of how Europeans were converted to Christianity, which includes both voluntary and involuntary conversions, as well as large differences between different regions, to the violent colonialization of native people by European empires, is not only ridiculous, but also very dangerous. Furthermore, the idea of Christianity as a foreign religion that does not belong to Europe has ties to antisemitic narratives, deeming Semitic religions as “evil invading forces” destroying “European culture.”[16]

This is a very complex issue and it is important to not simplify it, especially because it easily causes polemical discourses both against and for Heathenry and Neopaganism as a whole. The general public hardly knows anything about Neopaganism, let alone Heathenry, and the discourse on these religions remains largely polemical, either praising or completely problematising these religions. I’m concerned that the implicit ideas around roots within Heathenry will be further bent into suspect ideologies by far-right individuals, but I also do not want to further polemicise the discourse on Heathenry by depicting it as entirely problematic and right-wing. The diversity of Neopagan and more specifically even Heathen groups further complicates this discussion, as there tend to be politically very diverse groups across the globe with varying degrees of contact to each other. Depending from what angle you look at Neopaganism, you will see radically different movements, which of course can create bias in both directions. Scholars who have been mainly exposed to Neopaganism that concerns itself with environmentalism,[17] women’s rights[18] and that has ties to queer[19] and polyamorous[20] communities, might underestimate the danger of right-wing movements with a similar religious background that instead emphasise racial differences and “traditional family values.” Equally, scholars studying the latter might overlook this other side of Neopaganism, which can lead to the general public stigmatising people who have nothing to do with racist narratives.

In spite of this, I think that political differences in these movements are not merely different ways in which politics has been added to an original “positive” or neutral religious message, as it is often stated with regards to religions such as Christianity. Neopaganism is a group of modern religions that emerged out of political and societal narratives that are still relevant today. Compared to that, the original context in which Christianity emerged is completely foreign to us now. In all Neopagan religions that I’m aware of, environmentalism, which seems to have its origin in nature romanticism, and the notion of “re-enchanting the world”[21] is of a vital importance. This holds true regardless of other political notions. The theme of roots and ancestors is also very common, either used in a racist way, but otherwise often also along the lines of “going back to the roots,” living more “naturally” and occasionally of honouring supposedly more ancient matriarchal ideas. This focus on roots combined with the “invention of the (Neo)pagan tradition” often creates perceived connections to Indigenous religions,[22] which can be questioned from a postcolonial perspective. They can either lead to things like cultural appropriation[23] or, as I have shown, to a construction of an “ethnic ancestry” and claims of “indigenousness.”

Connecting Neopagan religions to the concept of “Indigenous religion” is something that is not entirely counterintuitive and has been done by some scholars studying politically more moderate movements under the umbrella of Neopaganism.[24] Their points are in so far logical, as these scholars apply a rather broad definition of what “Indigenous religion” means in their research. In spite of this, such scholarship still concerns me a little, because ideas around Indigenous religion can be easily bent into far-right narratives, like the ones I discussed in this blog entry. There are very intelligent people in all the various political camps of the Neopagan religions and Neopagans are generally encouraged to engage with primary (for instance medieval) and scholarly sources relating to their religion.[25] Because of this, scholarly sources and the way they engage with certain ideas and narratives within Neopaganism and Heathenry can have a great impact on these movements themselves. Postcolonial approaches where the concept “Indigenous religion” is also tied to a colonial history and colonial power structures might be valuable to this discussion.

To return to the Norns from the beginning: The roots I discussed here, are roots that should be watched carefully, but without polemical preconceptions. Our scholarly discourses can influence the way they grow. They might even determine how people connected to these roots will choose to shape their and our common future.

Source title image: An, Min. “Close-Up Photo of Green Caterpillar on Root.” Pexels, 7 Oct. 2018, www.pexels.com/photo/close-up-photo-of-green-caterpillar-on-root-1482818, (free stock photo).

[1] The Norns at the roots of Yggdrasil are specifically mentioned in the eddic poem Vǫluspá. The Old Norse poem can be found in different manuscripts such as the Codex Regius or the Hauksbók. Parts of it are also preserved in the Prose Edda. You can read these different versions of the poem online, see: “Sæmundar Edda by Sophus Bugge – Völuspá (Index).” Old Norse Etexts, Sophus Bugge, etext.old.no/Bugge/voluspa. Accessed 26 Feb. 2021. For a newer edition, you can also find the Vǫluspá of both the Hauksbók and the Codex Regius in the public catalogue of the Medieval Nordic Text Archive: “Public Catalogue.” Medieval Nordic Text Archive, 2021, clarino.uib.no/menota/catalogue. For an English translation see for instance: Crawford, Jackson. The Poetic Edda: Stories of the Norse Gods and Heroes (Hackett Classics). Indianapolis, Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 2015.

[2] See for instance: Meylan, Nicolas, and Lukas Rösli. Old Norse Myths as Political Ideologies: Critical Studies in the Appropriation of Medieval Narratives (ACTA Scandinavica). Turnhout, Brepols Publishers, 2020.

[3] Blain, Jenny, and Robert Wallis. “Heathenry.” Handbook of Contemporary Paganism (Brill Handbooks on Contemporary Religion), edited by Murphy Pizza and James Lewis, Leiden, Brill, 2009, pp. 413–32.

[4] Kaplan, Jeffrey. “The Reconstruction of the Ásatrú and Odinist Traditions.” Magical Religion and Modern Witchcraft, edited by James Lewis, New York, State University of New York Press, 1996, p. 199.

[5] Pike, Sarah. New Age and Neopagan Religions in America (Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series). Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series, New York, Columbia University Press, 2006, pp. 39-42.

[6] See for instance: Snook, Jennifer. „Reconsidering Heathenry: The Construction of an Ethnic Folkway as Religio-ethnic Identity.“ Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions, vol 16, nr 3,

2013, pp. 52-76.

[7] This can be shown by many different studies in the field of Psychological Anthropology, for instance. For an overview see: Piker, Steven. “Contributions of Psychological Anthropology.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, vol. 29, no. 1, 1998, pp. 9–31. Crossref, doi:10.1177/0022022198291002.

[8] “Neo-Völkisch.” Southern Poverty Law Center, 2020, www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/extremist-files/ideology/neo-volkisch.

[9] Azaola, Bárbara and Irene González. “La Comunidad Odinista de España Ásatrú.” Religion.Es: Minorías Religiosas En Castilla-La Mancha, edited by Miguel Hernando De Larramendi and Puerto García Ortiz, Barcelona, Icaria, 2009, pp. 311–13.

[10] Kaplan, “Reconstruction”, 1996, p. 226.

[11] Kaplan, “Reconstruction”, 1996, pp. 194-195.

[12] Gardell, Mattias. “Wolf Age Pagans.” Controversial New Religions, edited by Jesper Aa. Petersen and James Lewis, 2nd ed., Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2014, pp. 387–88.

[13] Narratives of being the victim within Heathenry are specifically discussed in Thad N. Horrells article: Horrell, Thad. „Heathenry as a Postcolonial Movement“. The Journal of Religion, Identity, and Politics. nr 1, pp. 1–14. Ideas of victimhood are also present in other Neopagan movements such as Wicca, where some practitioners identify with the victims of the witch burnings. See for instance: Shuck, Glenn. “The Myth of the Burning Times and the Politics of Resistance in Contemporary American Wicca.” Journal of Religion & Society, vol. 2, 2000, pp. 1–9. Wikimedia, upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/bd/The_Myth_of_the_Burning_Times_and_the_Politics_of_Resistance_in_Contemporary_American_Wicca.pdf.

[14] Kraemer, Christine Hoff. “Gender and Sexuality in Contemporary Paganism.” Religion Compass, vol. 6, no. 8, 2012, pp. 390–401. Crossref, doi:10.1111/j.1749-8171.2012.00367.x.

[15] The clearest example for this is a group of people that label themselves as “ChristoPagan” which in this context means following both Christian and Neopagan religious traditions and is not to be confused with the same term meaning pagan, rather than Jewish converts to Christianity in antiquity. I have not come across any scholarly sources on this particular phenomenon, but you can find many practioners who describe this religion online or even in books. See for instance: Higginbotham, Joyce and Higginbotham, River. ChristoPaganism: An Inclusive Path. Woodbury, Llewellyn Publications, 2009. or check out the ChristoPagan reddit community: “Christopaganism • r/Christopaganism.” Reddit, 2020, www.reddit.com/r/Christopaganism.

[16] Such narratives were especially common in the ideology of the Third Reich, where the „German race“ was bound to fight against „Jewry and Asians“. To win such a conflict, Heinrich Himmler promoted a de-Christianisation combined with a Germanisation of the Third Reich. See for instance: Longerich, Peter. Heinrich Himmler. Reprint, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2013, pp. 261-266.

[17] Even though not all Neopagans are active environmentalists, the religious and political narratives in most, if not all Neopagan religions, underlign the importance of the natural environment and at least imply environmentalist concerns and activism. Environmentalist activism certainly is an important aspect of the religious life of some practioners. See for instance: Berger, Helen. “Contemporary Paganism by the Numbers.” Handbook of Contemporary Paganism (Brill Handbooks on Contemporary Religion), edited by James Lewis and Murphy Pizza, Leiden, Brill, 2009, pp. 162–66.

[18] Kraemer, “Gender and Sexuality“, pp. 390–401.

[19] ibid.

[20] ibid.

[21] Puckett, Robert. „Re-Enchanting the World: A Weberian Analysis of Wiccan Charisma.“ Handbook of Contemporary Paganism (Brill Handbooks on Contemporary Religion). Edited by Lewis, James and Pizza, Murphy. Leiden: Brill, 2009, pp. 121-151. For an overview of the narrative of “disenchantment” also see Josephson-Storm, Jason. The Myth of Disenchantment: Magic, Modernity, and the Birth of the Human Sciences. Chicago. University of Chicago Press, 2017.

[22] See for instance: Snook, „Reconsidering Heathenry“

2013, pp. 52-76.

[23] Magliocco, Sabina. „Reclamation, Appropriation and the Ecstatic Imagination in Modern Pagan Ritual.“ Handbook of Contemporary Paganism (Brill Handbooks on Contemporary Religion). Edited by Lewis, James and Pizza, Murphy. Leiden. Brill, 2009, pp. 235-238.

[24] See for instance: Owen, Suzanne. „Druidry and the Definition of Indigenous Religion“. Critical Reflections on Indigenous Religions. Edited by Cox, James. London. Routledge, 2016, pp. 81-92. or Puca, Angela. “Is DRUIDRY Indigenous? What Is an Indigenous Religion?” YouTube, 29 Nov. 2020, www.youtube.com/watch?v=ubQC33GKfbM.

[25] Stefanie von Schnurbein discusses this specifically in relation to Germanic Neopaganism: Von Schnurbein, Stefanie. „Tales of Reconstruction. Intertwining Germanic neo-Paganism and Old Norse Scholarship.“ Critical Research on Religion, nr 3(2), 2015, pp. 148–167.

1 Kommentar