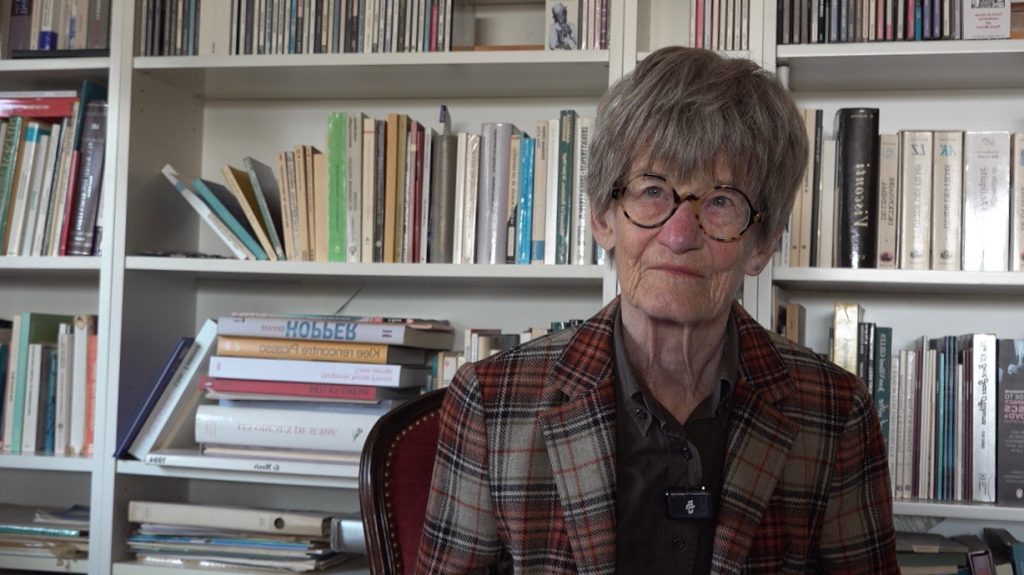

Ursula Nordmann grew up in a family environment marked by profound ruptures but also by decisive support. The daughter of a country doctor and one of four siblings, she experienced her parents’ separation at the age of four. From then on, she lived with her mother in Zurich, in a small apartment in her grandparents’ house. Despite an undiagnosed dyslexia at the time, she successfully completed her schooling in Zurich by developing her own strategies to overcome this obstacle. Thanks to her uncle’s support, she was able to spend holidays in the mountains and learn to ski – experiences that shaped those early years in a positive way.

After completing her Matura, she followed her uncle’s advice and began studying in St. Gallen with the goal of later working at his bank. Several international internships in Paris, London, Monaco, and Geneva complemented her economics education and offered her valuable insights. When the bank went bankrupt and her uncle passed away, her future plans dissolved abruptly, and she was forced to assert herself in a labor market that offered women in economics few opportunities. Refusing to be reduced to the role of an executive secretary, she eventually found a position with an economic journalism editorial team.

In 1968, an offer from her professor fundamentally changed the course of her career: she became an assistant for the editorial team of the Zurich Commentary on the ASA. She worked in this role for fifteen years, which enabled her transition into the field of law. Alongside her job, she studied law, specializing in particular in economic law, started a family, and opened her own law firm after obtaining her bar certificate. In 1994, she was appointed full professor of economic law at the University of Neuchâtel, before being elected to the Federal Supreme Court in 1996, where she served as a judge until 2007.

Her commitment, however, extended far beyond academia and the judiciary. From 1984 to 1990, Ursula Nordmann was a member of the Federal Commission for Women’s Issues, where she contributed to major reforms: the new matrimonial law, the revision of divorce law, the introduction of splitting in the second pillar, and the tenth revision of the AHV. Her expertise shaped preliminary drafts, consultations, and political debates that were central to advancing gender equality in Switzerland. She also engaged in legal public education, firmly believing that democracy can function only if the population understands what it is voting on.

As a lawyer, professor, commission member, and later Federal Supreme Court judge, Ursula Nordmann embodies a generation of trailblazing women who, with perseverance, precision, and a strong sense of public service, enabled significant progress in Swiss gender equality law. Her life path, marked both by profound personal losses and remarkable tenacity, demonstrates impressively how individual commitment can sustainably inspire societal change.